Welcome to this Sunday, the end of the church’s liturgical year. Next week is the start of a new calendar with the season of advent and its build up to Christmas. For the last 50 years or so, this Sunday has been a celebration of the Feast of Christ the King or, as it is called in the Methodist lectionary, the Reign of Christ. This year is also the 100th anniversary of Pope Pius XI’s encyclical (letter to the churches) after the First World War, which was subtitled “On the Peace of Christ in the Kingdom of Christ”. These themes will be the basis of the today’s service.

Interestingly, several of the more senior people in this congregation have said to me, on hearing that I was scheduled to lead the reflection today, “Oh dear, well never mind, you can always find something else to talk about”! I guess it doesn’t sit easily with progressives, or perhaps with Methodists. That of course made me all the more curious to see what I could find to say about the topic, and I think it resonates with Garth’s recent summaries in AngelMail from Marcus Borg’s book, “Speaking Christian”, in which Borg suggests we have seriously misunderstood key Christian concepts, and need to take another look; we need to recognise the importance of words, how titles can come to define meaning, and how that meaning can change with time. So, this morning I am going to delve a little into the origins of attributing kingship to Christ and then pose a question.

‘“The days are coming,” declares the LORD, “when I will raise up for David a righteous Branch, a King who will reign wisely and do what is just and right in the land.”’ The passage we heard from Jeremiah expressed a hope for freedom, iron-age style freedom, when safety came from having a strong leader to organize and protect your tribe from the threat posed by neighbouring tribes. The book of Jeremiah addresses the woes of the Israelites in the southern Kingdom of Judah, building up to the fall of Jerusalem to the Babylonians, and the destruction of the first Temple (Solomon’s), around 600 years before Jesus’ prophetic ministry. The author looked back to the “golden days” of King David’s reign, around 400 years earlier, and yearned for a new king to lead the Israelite people to freedom.

The passage from Jeremiah may have been written about long distant events, but the theme would have been all too familiar to the Israelites of the First Century AD, and is echoed in the passage from Luke, in which Zechariah, the father of John the Baptist, sings “He has raised up for us a horn of salvation in the house of David his servant. This is what he promised in the words of his holy prophets of old: deliverance from our enemies, and from the hands of all who hate us”. The gospel of Luke was probably written down in its current form around the end of the First Century, and fresh in the compiler’s memory would have been the destruction of the second Temple (Herod’s), this one by the Romans in 70 AD. There is no doubt that in both Jewish and early Christian communities, who were still very closely related in those years, there was a yearning for a new king who would turn over the world order and restore the relationship between God and God’s people, the Israelites. We know from Romano-Jewish historian, Josephus, that there were a dozen or more messianic or would be messianic movements within a hundred years either side of Jesus A. Messiah, meaning ‘the anointed one’ (in this context a new king) and translated to English from the Greek as Christ.

Of course, the reality of kings was very different from this aspirational vision. The Israelites had been warned in the past not to have a King. After their escape from Egypt, the Israelites formed a loose confederation of tribes under a series of military/political leaders called Judges. The last of these was Samuel, who defeated their old foe, the Philistines, and ushered in an era of peace, but his sons failed to follow in his footsteps and the Israelites called for a king “such as other nations have” (1 Sa 8:5). Picking just a few of the privileges which Samuel warns a king would demand of them: ““This is what the king who will reign over you will claim as his rights: He will take your sons and make them serve with his chariots and horses, and they will run in front of his chariots…. 14 He will take the best of your fields and vineyards and olive groves and give them to his attendants…. 16 Your male and female servants and the best of your cattle and donkeys he will take for his own use. 17 He will take a tenth of your flocks, and you yourselves will become his slaves” (from 1 Samuel 8:10-18).

Naturally the Israelites ignored his warning, so Samuel anointed Saul as king and after a bit of to-ing and fro-ing the people agreed to follow Saul because he won a great battle against another enemy tribe, the Ammonites. After Saul came David, and after David, Solomon (he who built the Temple). That short period of around 100 years was the Golden Age to which the Israelites looked back with longing for the next thousand! Even the great king they looked back on, David, was not a good man. His life story appears twice in the Bible. Jonathan Kirsch, an editor of The Jewish Journal says “David’s story was so scandalous it had to be censored…The Book of Samuel is the first and unexpurgated version, chock full of sexual and physical violence, passion, scandal, dysfunction, and outrageous moral excess. The Book of Chronicles, composed and added to the Bible at a later date, preserves a wilfully censored version that depicts David as a much milder, tamer and more pious figure.” B

Ah, but so what? This is not the kind of king we are talking about, is it? We are talking of a perfect king; one who showed us that the greatest was the least and that peace, not violence was the way. While that strand of thought was present in the Hebrew scriptures, particularly from the prophets Isaiah and Zechariah and Micah, we must acknowledge that there was also a significant strand of prophetic vision of a king who would regain God’s favour and throw out and defeat their enemies in battle, and re-establish Israel as top-dog.

Paul of Tarsus, who wrote so much of our New Testament, had his own struggle with this. Raised in a strict Jewish tradition, he started by suppressing any suggestion that Jesus could have been the expected Messiah. But his experience of the resurrected Jesus led him to become a most ardent preacher of a gospel which NT Wright summarises as: the gospel “promised beforehand in holy scripture”, whose “central figure is one who was from the seed of David and [who was] now marked out as the Son of God.” Paul and subsequently the writers of the Gospels had come to understand a much broader view which saw God’s promise as not just to rescue the Israelites from the Gentiles, but to bring the God of Israel’s reign to the Gentiles, to the pagan world. Paul does not use the word King in our translations but talks of Jesus “at God’s right hand” (a description used of David) and primarily uses the titles “Lord” and “Christ”. Lord, a term used in the Hebrew bible when addressing God or the King, but also used in the Roman Empire as a term for the emperor, and Christ, the anointed.

Luke’s Gospel takes a more Romano-Greek literary approach to portray Jesus’ kingship. In the great advent and Christmas story which Luke inserts at the start of his gospel, he ties together a series of portentous events using three “hymns”:

- Mary’s song, the familiar Christmas story of an angel foretelling Jesus’ birth: “You will conceive and give birth to a son, and you are to call him Jesus. 32 He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High. The Lord God will give him the throne of his father David, 33 and he will reign over Jacob’s descendants forever; his kingdom will never end.” (Luke 1:30-33)

- Zecharaiah’s Song which we heard in today’s reading

- And Simeon’s Nunc dimittis – Simeon, a devout Jew who had been promised by the Holy Spirit that he would not die until he had seen the Messiah.

This combination stages a clear announcement of Jesus’ credentials. Much later in the Gospel Luke describes the Palm Sunday crowd greeting Jesus with cries of “Blessed is the King who comes in the name of the Lord”, at his trial before Pilate, Jesus is asked “are you the king of the Jews?”, a charge echoed in Acts 17:7, where Paul and Silas are accused of “defying Caesar’s decrees, saying that there is another king, one called Jesus”.

A king, in biblical days, was someone to whom you pledged allegiance, of whom you were in awe, whom you worshipped, often literally, and who in return organised protection and advancement of your people. So, to the question: Is it still appropriate, or even helpful, to apply the title King to Jesus? I am not alone in asking this. In a 2013 homily, American social activist and retired Catholic Bishop, Thomas Gumbleton says “the Feast of Christ the King [is] probably one of the most… direct contradictions of the way of Jesus as we could find to celebrate.” C

Names, titles, are important; they conjure up meaning. I’m sure many of us have experienced being called names, whether the direct type of name-calling at school or the more subtle ways adults use to categorise, denigrate and exclude. No doubt we all call ourselves names at times, sometimes deservedly but in our dark places we can end up believing our own low opinions of ourselves. At the other end of the spectrum, positive words can build confidence and self-respect. But a title can take on a life of its own, from the cultural associations of the word. What does the word, King, bring to mind for you? This year, it probably draws a picture of pomp and pageantry, slightly ridiculous military dress uniforms and miles of gold braid. Bishop Gumbleton suggests that there are three things we identify with kingship: “Kings have power; kings have wealth; kings lorded over others…. With Jesus, none of these is true.”

The Bishop goes on to say: “I think we must acknowledge that in so many ways, this idea of Jesus being a king goes against the genuine way of Jesus because he rejected power over others. He wanted to be the slave, the servant of all. He rejected excessive wealth; he wanted everyone to share in the goods of the world that God made for all, and not for a few…. Above all, Jesus rejected violence…. He was willing to suffer rather than inflict suffering; willing to be killed rather than kill, because he knew that the way of active love was the only way to transform our world into the reign of God.” Well said.

Think about Jesus’ response to his disciples when they asked who would be the greatest (Luke 9:48 “…it is the one who is least among you all who is the greatest.”, or the example he set by washing his disciples’ feet (John 13:14 “Now that I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also should wash one another’s feet.”). And what was Jesus’ response to Pilate’s question, “Are you the King of the Jews?”? Well, it depends a bit on which translation or paraphrase you are using but the original Greek is constructed to indicate Jesus replies, “So you say”, on the basis of which Pilate finds he has done nothing wrong. Any confirmation by Jesus of kingship is a later construction.

Think about Jesus’ advice to a wealthy young man (Mark 10:21 “Go, sell everything you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven.”), or his lifestyle as an itinerant preacher, which he passed on to the disciples (Mark 6:8-9 “Take nothing for the journey except a staff—no bread, no bag, no money in your belts.”), his attitude to food and possessions in Matthew and Luke’s collections of his teaching (Luke 12:22-23 “Do not worry about your life, what you will eat; or about your body, what you will wear. 23 For life is more than food, and the body more than clothes”, Luke 12:33 “Sell your possessions and give to the poor. Provide purses for yourselves that will not wear out, a treasure in heaven that will never fail”).

Despite this contrast, the idea of Christ the King has great appeal. However much I disagree with the theology of hymns like the one we just sang (Crown him with many crowns) they are uplifting to sing! But words can be tricky things. What starts as a description, or even an analogy, can become a definition and as the meanings of words change over the centuries so that definition moves further from its original intent.

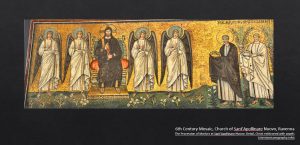

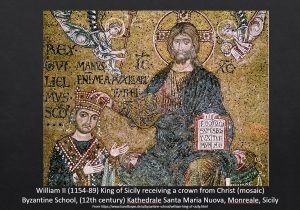

We can see in art how quickly the use of the term king for Jesus came to alter perceptions. The earliest preserved depictions show Jesus as shepherd, or portrayed in the style of a philosopher – sometimes as a beardless youth in roman tunic, sometimes long-haired and bearded. From around the middle of the 4th Century Christian imagery started to develop a new tradition of regal poses and costumes modelled on Roman Imperial iconography. And just as the images of Jesus took on the form of earthly kings, so the earthly kings took the Christ as a heavenly justification for their power. The example from a mosaic of the 12th Century shows a stern and proud-faced Christ, seated on a golden throne studded with gems crowning William II of Sicily.

We can see in art how quickly the use of the term king for Jesus came to alter perceptions. The earliest preserved depictions show Jesus as shepherd, or portrayed in the style of a philosopher – sometimes as a beardless youth in roman tunic, sometimes long-haired and bearded. From around the middle of the 4th Century Christian imagery started to develop a new tradition of regal poses and costumes modelled on Roman Imperial iconography. And just as the images of Jesus took on the form of earthly kings, so the earthly kings took the Christ as a heavenly justification for their power. The example from a mosaic of the 12th Century shows a stern and proud-faced Christ, seated on a golden throne studded with gems crowning William II of Sicily.

It was not just the secular authorities. The church took the same approach of using the image of Christ the King blessing those they favoured – in this example Christ sits crowned and enthroned as he receives the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Dominican kneeling before him, who is being presented to him by the Virgin Mary (also crowned). This was the world they lived in. This was how power worked. To be associated with kings was to gain some of their mana. Sadly this is not confined to the Middle Ages. Think of the absurd scenes of evangelical pastors praying over Trump.

It was not just the secular authorities. The church took the same approach of using the image of Christ the King blessing those they favoured – in this example Christ sits crowned and enthroned as he receives the writings of St. Thomas Aquinas, the Dominican kneeling before him, who is being presented to him by the Virgin Mary (also crowned). This was the world they lived in. This was how power worked. To be associated with kings was to gain some of their mana. Sadly this is not confined to the Middle Ages. Think of the absurd scenes of evangelical pastors praying over Trump.

In his book “Speaking Christian” Marcus Borg describes the book’s purpose as to go back to “more ancient and authentic meanings” of Christian language, drawn “from the Bible and pre-modern Christian tradition”. But as we have seen, even in Jesus’ time and earlier, scriptural interpretation was not uniform – there was a tension between the military expectations of liberation, and the vision of a loving Creator. From Psalm 89, for example, which mourns Israel’s loss of God’s favour in battle we have both: “Righteousness and justice are the foundation of your throne; love and faithfulness go before you.” (vs. 14) and “I have bestowed strength on a warrior; I have raised up a young man from among the people…. I will crush his foes before him and strike down his adversaries.” (vs.19, 23).

Conflicting imagery derives from the merging of the kingly title and the messianic expectations in early Christian writings, such as the book of Revelation where “the Lamb” (a symbol of Christ) is to be king of kings, lord of lords (17:14). The text develops this theme by portraying Christ as the rider of a white horse in chapter 19, one who is particularly unlike the Jesus of the gospels: “I saw heaven standing open and there before me was a white horse, whose rider is called Faithful and True. With justice he judges and wages war.…. 15 Coming out of his mouth is a sharp sword with which to strike down the nations…. He treads the winepress of the fury of the wrath of God Almighty. 16 On his robe and on his thigh he has this name written: KING OF KINGS AND LORD OF LORDS. (Rev 19:11-16)

How does this fit with the story of Palm Sunday in which Jesus chooses to enter Jerusalem riding on a donkey, symbolic of the peaceful vision of the Old Testament prophet Zechariah? (‘See, your king comes to you, righteous and victorious, lowly and riding on a donkey, on a colt, the foal of a donkey. 10 I will take away the chariots from Ephraim and the warhorses from Jerusalem, and the battle bow will be broken. He will proclaim peace to the nations.’ (Zechariah 9:9-10). Again, this is not all in the past – the bloodthirsty visions in the book of Revelation remain exceedingly popular with some Christian churches, particularly in the US. Someone has even written a children’s story of Jesus, the rider on the white horse. Which of these images would you prefer to teach your children, or grandchildren?

The early Christian church inherited prophetic visions that God had made promises, to Abraham of an everlasting covenant with his descendants, and to David that a king would follow from his line whose house and kingdom would endure forever (2 Samuel 7:16). This “chosenness” is at heart a form of tribalism, which has developed in some lines of Christian thinking to “supremacy” in which a narrow understanding of Christ, as King of kings, to whom all the nations will bow down, must be foremost and exclusive.

It is hard to reconcile this tribal view, from an era when people knew very little beyond their own limited horizons, with our far broader modern experience of the world, our multicultural, multifaith awareness. Pope Pius XI, who instituted the Feat of Christ the King, observed that the recent First World War had not brought true peace, and to counter that, the Church and Christianity should be active in, not insulated from, society. He suggested that patriotism was “the stimulus of so many virtues and of so many noble acts of heroism when kept within the bounds of the law of Christ” but became merely “an added incentive to grave injustice when true love of country is debased to the condition of an extreme nationalism, when we forget that all men are our brothers and members of the same great human family”. Yet, if I dare criticize a Pope, when he made the claim true peace could “only be found under the Kingship of Christ”, or when Christianity claims that Christ must be King of kings, this too can become just another form of the extreme tribalism he criticizes.

Well, you can guess my answer to my own question! It may not be the same as yours, and that’s fine. I see this church as a place where we can openly discuss and explore those key Christian concepts. Am I being heretical? Perhaps, but Brian McLaren writes in his most recent book, Should I stay Christian: “Wouldn’t an evolving Christianity have an option beyond being forever ruled by authoritarian patriarchs who demand adherence to an outdated conceptual universe?… Might we, far from being disloyal heretics, actually have the opportunity to become the evolutionary descendants of Jesus, who are called to carry on his radically progressive vision in our brief time on this earth?” We shouldn’t hide the past, or re-write history, but we have to acknowledge it and move forward. McLaren suggests our faith and understanding grow, not in a linear fashion discarding the past and moving on, but like a tree grows – “Each growing season, a tree adds a ring. The new ring doesn’t exclude the previous rings; it embraces them in something bigger. It includes and transcends…. We are not defined exclusively by who we came from in the past. We can also be defined by what we can become in the future.” And that can be a thing of beauty.

References:

- NT Wright, What Paul Really Said

- Fourteen Things You Need to Know About King David | My Jewish Learning

- (Jesus is a king, but not a king in the world’s definition | National Catholic Reporter (ncronline.org))