What do you first think of when I say the word, “nature”? As in, “the natural world”. Is there a special place where you feel close to nature? The natural world has the capacity to comfort us; its beauty can be breathtaking! Nature can appear with a majesty which inspires awe, but it is supremely indifferent to our existence, reminding us of the fragility of life. Let us not romanticise it. The natural world is also “red in tooth and claw”. It is no fun being a herring when pursued by a hungry orca. There is nothing romantic in becoming a cheetah’s dinner.

How would you define the word, “nature”? An article in The Guardian last month raised the question as it reported on an attempt to change the primary definition in the Oxford English Dictionary, which reads:

Nature is “a. The phenomenon of the physical world collectively; especially plants, animals and other features and products of the earth itself, as opposed to humans and human creations”.

The activist proposing this change said, “It got me thinking: if people feel we’re separate from nature, how can we really consider nature in our actions? This definition and worldview is just so much to do with the crisis that we’re in.” The activist won this battle and got the Dictionary to make another definition visible online as well.

“b. More widely: the whole natural world, including human beings.”

Do you see yourself as part of nature? When you go tramping, is it the pleasure of the latest hi-tech equipment protecting you from the elements? If you go fishing or hunting, do you see it as pitting yourself against the elements? Is gardening a constant battle against nature? Or does the enjoyment come from the feeling of being immersed in the natural environment? Perhaps both?

The book, “Sacred Nature”, by Karen Armstrong, considers how we can rekindle our spiritual bond with nature by drawing on the wisdom of the world’s religious traditions. Karen Armstrong started as a Catholic nun, but left the order after seven years to study English and commenced a forty-year career as a writer and broadcaster focussing on historical understandings of God and comparative religion.

Karen suggests that “…people in early civilisations did not experience the power that governed the cosmos as a supernatural, distant and distinct ‘God’. It was rather an intrinsic presence that they… experienced in ritual and contemplation – a force imbuing all things, a transcendent mystery that could never be defined.” Monotheism, the belief in a single God that is central to the faith of Jews, Christians and Muslims, she suggests, was the great exception to this view of God: “The Hebrew Bible does not focus on the sanctity of nature, because the people of Israel experienced the divine in human events rather than in the natural world.”

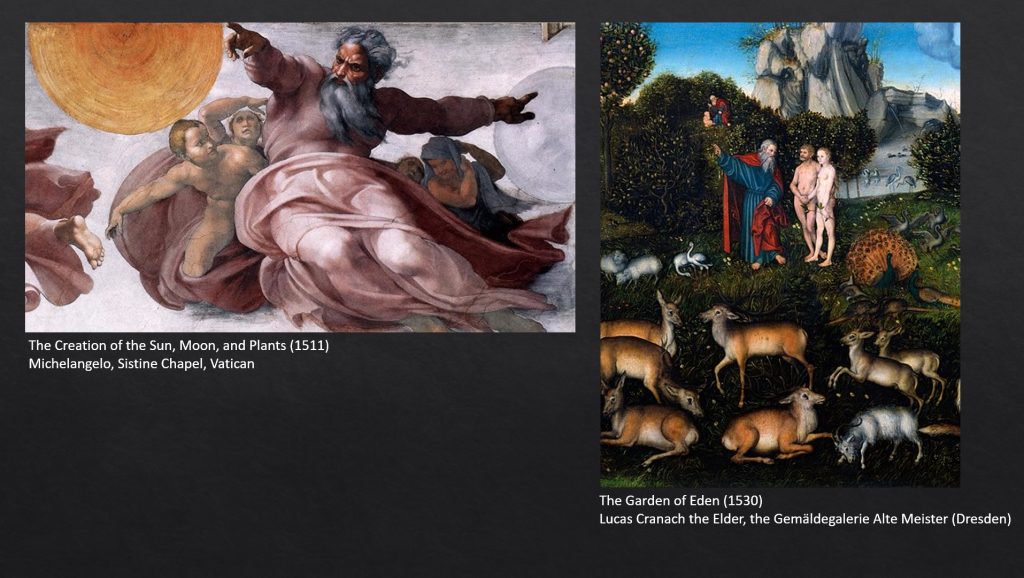

As you probably already know, the book of Genesis contains two distinct creation stories. In the first of these, of which we heard just the beginning earlier (the beginning of the beginning!), God speaks and the physical world takes shape from chaos. The second story has a more hands-on God who works with the earth like a potter, walks in the garden and talks with Adam and Eve.

Karen Armstrong uses the term “mythos”, for this kind of thinking. Mythos is concerned with meaning not practical affairs. It addresses what is considered timeless, looking both back to the origins of life and culture and inward to the deepest levels of human experience. In contrast to mythos, “logos” is wholly pragmatic: it is the rational mode of thought that enables human beings to function, by which we make things happen.

Karen Armstrong uses the term “mythos”, for this kind of thinking. Mythos is concerned with meaning not practical affairs. It addresses what is considered timeless, looking both back to the origins of life and culture and inward to the deepest levels of human experience. In contrast to mythos, “logos” is wholly pragmatic: it is the rational mode of thought that enables human beings to function, by which we make things happen.

I like the use of the Greek word, mythos, as it is free from the associations we may have for words like “story” and “myth”, which can imply a lack of truth, or even entertainment – as in, “it’s just a story”. Make no mistake, these are not just stories. There is a power to mythos. Consider the current politico-religious debate in the USA. Much of what is put forward as logical argument is derived from mythos rather than logos. For example, the mythos of American male identity (what has been called John Wayne Christianity), or the mythos of when life begins in the human reproductive process.

While some see mythos and logos as separate, I think they are closely linked and often overlap in practice. Early in the church’s history, logical reasoning developed hand in hand with the idea that God could be seen in the world through his works, through creation. This idea is seen in the creation stories and reinforced in Hebrew writings such as the Psalm we heard earlier: “By the word of the LORD the heavens were made, and all their host by the breath of his mouth….” (Ps 33: 6). Early Christian writings supported the view that God could be seen through the natural world. In today’s reading from the letter to the Romans Paul writes that “Ever since the creation of the world, God’s eternal power and divine nature, invisible though they are, have been seen and understood through the things God has made.” Art Dewey and his co-authors of “The Authentic Letters of Paul” explain that Paul is using “an argument based upon the Jewish stereotype of the non-Jew”. The use of images in worship was anathema to the Jews and evidence, in their thinking, of the fallen nature and cause of the uncivilised behaviour of the gentiles. The Jesus followers in Rome included gentiles – former followers of the Roman, Greek and other polytheistic religions – and Paul is saying they had no excuse; they should have recognised the true God through his works of creation.

By the early 14th Century mythos and logos were entangled in the early universities and divinity schools. By that time, students at the universities of Paris, Oxford and Bologna were studying logic, mathematics and Aristotelian science before they began their theological studies. When they arrived in divinity school, they were so well versed in logical thought that they instinctively tried to describe theological issues in rational terms – logical “proofs” of God, for example.

In the 16th Century, the English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561–1626) went a step further, by arguing that human beings could discover the laws that governed natural forces and would then be able to exploit nature for their own benefit. For Bacon, God had given Adam clear instructions to ‘fill the earth and conquer it’, but God’s original plan had been foiled by Adam’s disobedience. It was now time for philosophers to repair the damage wrought by the Fall and for humans to break with the ingrained – the pagan – habit of revering nature.

Here’s another definition for you, this one from Wikipedia: “The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics [and science] transformed the views of society about nature.” But this transformation and the social transformations that followed during the European “Age of Enlightenment”, did not develop in a vacuum. From Copernicus to Newton, European scientists were to, one extent or another, Christian even if elements of their work brought them into conflict with the authorities. Science developed within the cultural matrix of the Christian mythos of its time. And with regard to creation, Genesis 1 was the dominant mythos for most of that development. So mythos and logos danced through the centuries like a salsa – one moment looking into each others’ eyes, the next, flinging their partner to arm’s length and leaning backwards as if to get away!

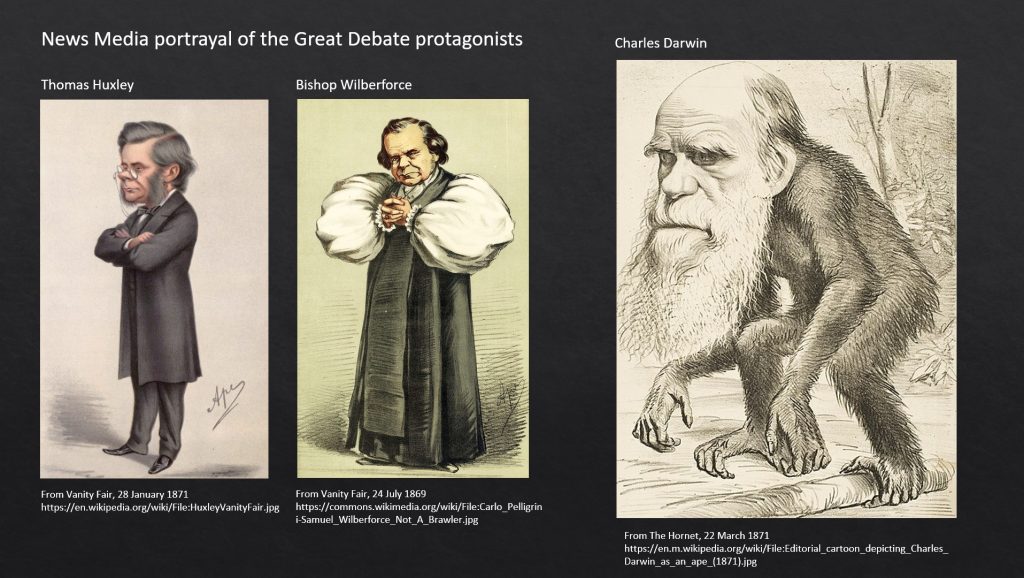

As science drew away from religion and God became a superior kind of mechanic or a physical phenomenon, the creation mythos remained embedded: nature became a resource to be exploited. Ironically, it was science which started to put man back into context in the natural world with Darwin’s study of evolution, and the Christian church which stood implacably in its way. In 1860, the Museum of Natural History in Oxford hosted what became known as the Great Debate, between biologist, Thomas Huxley, and the Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce. The topic – evolution by natural selection. Darwin’s book, On the Origin of Species, had been published the previous November so the ideas were fresh and the topic highly controversial. The debate remains famous in part for a question from the Bishop as to whether Huxley had any preference for his descent from an ape being on his father’s side or his mother’s! A cartoon was subsequently published in a satirical magazine, showing Darwin as “a venerable Orang-utang”!

As science drew away from religion and God became a superior kind of mechanic or a physical phenomenon, the creation mythos remained embedded: nature became a resource to be exploited. Ironically, it was science which started to put man back into context in the natural world with Darwin’s study of evolution, and the Christian church which stood implacably in its way. In 1860, the Museum of Natural History in Oxford hosted what became known as the Great Debate, between biologist, Thomas Huxley, and the Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce. The topic – evolution by natural selection. Darwin’s book, On the Origin of Species, had been published the previous November so the ideas were fresh and the topic highly controversial. The debate remains famous in part for a question from the Bishop as to whether Huxley had any preference for his descent from an ape being on his father’s side or his mother’s! A cartoon was subsequently published in a satirical magazine, showing Darwin as “a venerable Orang-utang”!

In the modern era of Carl Sagan and David Attenborough, James Hansen and Michael Mann, it seems that science has all the answers if we just listen. Does religion have any relevance in understanding the environment? Well, we have to ask the question why, when faced with overwhelming evidence of man-made climate change and proven routes to avert ecological disaster, do we not listen to the science? Perhaps the answer comes back to the difference between logos and mythos. Humans need an underlying meaning to life to frame their actions. Our world view is currently permeated by economic theories of consumption and exploitation, of resources that are used as if inexhaustible and, when found to be limited, resources that must be fought over for control. And that world view comes at least in part, and behind the scenes, from the hierarchical Christian view of the world order. God at the top, humans next, and below them the rest of his creation. As the Psalm for today goes on to say “The LORD looks down from heaven; he sees all humankind. From where he sits enthroned, he watches all the inhabitants of the earth” (Ps 33:13-14).

Fortunately, there has always been a diversity of thought within the Judeao-Christian tradition. Alternative thinking, often from the mystical traditions, has continually returned to the idea that God is not is not separate from creation, and that humans are not separate from the natural world. In John Caputo’s terms, these are radicals. John Caputo is another author who started life with very traditional Roman Catholic views but grew away from them and became a philosopher. Radical, John Caputo says, means rethought, restaged, reimagined, reinvented, all in an effort to get at what is really going on.

Surprisingly enough, given the diatribe against idolatry we heard earlier, the Apostle Paul is one of the earliest attributed with views seen by Caputo as radical. In the Acts of the Apostles, Paul is described as visiting Athens where he is invited to present his “new teaching” to the local philosophers. In his speech, Paul says that all peoples have an innate desire to search for God, but they do not need to look far, for “in him we live and move and have our being”. (Acts 17:28). Another surprising inclusion in the list is Augustine of Hippo, the 4th Century theologian, who deservedly receives criticism from progressive thinkers for his views on original sin (as well as sexism, antisemitism and self-loathing). However, Augustine also wrote: “Do not wander far but return to yourself; truth dwells deep within man.”

The 13th Century theologian, philosopher and mystic, Meister Eckhart, wrote in one of his Sermons, “The eye through which I see God is the same eye through which God sees me; my eye and God’s eye are one eye, one seeing, one knowing, one love.” There are elements of this thinking in John Wesley’s sermons too. “The pure of heart see all things full of God.”, he wrote in 1872. “They see him in the firmament of heaven, in the moon walking in brightness, in the sun when he rejoiceth as a giant to run his course.” (Sermon 23, Upon our Lord”s Sermon on the Mount Discourse 3, 1872)

Celtic Christianity, which developed on the far fringes of the old Roman Empire, lived more comfortably with elements of the local pagan religions. This outpost of Christianity arrived with the Romans possibly as early as the First Century and retained its distinct character after their retreat through to the Early Middle Ages. There have been several revivals of Celtic Christian traditions (by radicals!) through the centuries, including that centred on the Island of Iona in the 20th Century. One of the principles of Celtic Christianity is the belief that nothing is secular because everything is sacred. The author Esther de Waal, in her book Every Earthly Blessing, writes “The Celtic approach to God opens up a world in which nothing is too common to be exalted, and nothing is so exalted that it cannot be made common.” This view that sees God in everything, encourages a reverence for God’s creation and a respect for the care of his world.

One hero of John Caputo’s book on radical theology, a big thinker whose work underpins Caputo’s, is Paul Tillich – a 20th Century philosopher and Lutheran theologian. Tillich described God as “the unconditional”, that which is there before even thought and which cannot be shut up inside a word or a being, not even a Supreme one. By definition, we cannot describe God, and yet we are bound to try to do so because we cannot think about God except through use of language. Talking about God ultimately comes down to images and figures, metaphors and metonyms, symbols and allegories, parables and paradoxes, stories and striking sayings, songs and dance. As Cynthia said a couple of Sundays ago, Jesus was a great poet and we should not take poetic descriptions literally. John Caputo calls this theopoetics (as opposed to theology).

Taking a metaphor from John Caputo’s book, there are two kinds of theologians: there are the bridge-builders, who see God as on high and think we must build a bridge from the world to God (using such ideas as salvation and substitutionary atonement); and there are the ground diggers, who believe that God is the very ground on which we stand, but that we have to do a bit of digging (thinking) to see it. The bridge-builders think we have to find some way to attain the truth. The ground-diggers think we are already in the truth, that God is truth, and that the task is to unearth its truth; they are the theo-poets.

When we describe God as a being, however Supreme, we limit God. Tillich talks of looking for “God beyond God” (beyond the symbols we use to define God), but he does not mean God transcending space and time. Rather he means seeking the ground of being which is deeply embedded in space and time. “Beyond” does not mean up but down; it does not mean higher but deeper; it does not mean farther but closer. More humorously, John Caputo writes “If we were all aquatic creatures, God would be the water, not the biggest fish in the sea.”

Traditional Christianity has always been suspicious of this kind of thinking, which is seen as too close to pantheism. Another definition for you – Pantheism “identifies God with the universe or regards the universe as a manifestation of God”. As I said earlier, in today’s reading from letter to the Romans, Paul rages against confusing God with images, with material things (1:22-23). First Judaism and then the emerging Christianity stood apart as monotheistic religions in a world dominated by polytheism. God was the Creator and not to be confused with Creation. Although Christianity has subsequently tied its theology in knots to incorporate the concept of the Trinity, it has difficulty with numbers greater than three. Christianity is comfortable with the idea that we see Christ in people that we meet, but less so with seeing God in the things we see around us. Nature as a kind of signature of God, yes. God present in nature, not so much. But is it really so far from Paul’s reference to God “in whom we live and move and have our being”?

John Caputo suggests that pantheism is seen as atheism (or worse!) by the traditional church. Which is ironic since one sees God in everything and the other sees no God at all. He prefers the word “Panentheism”, which by that extra syllable emphasises the in-ness of God – “All in God” – and so avoids having to explain what you don’t mean by pantheism!

I’m sure I would be preaching to the converted if I said we must act now to stop the environmental destruction humans are causing on the planet. But I hope that I have given some pause for thought about how we communicate that within the church and to those in the secular world. The concepts, the mythos, we use to express why Christians should feel strongly about this are important. Much of what is preached, using biblical thinking from 2000 or more years ago, is simply unbelievable to those outside the church. As a scientist, I am uncomfortable using the expression God’s creation when I certainly don’t mean that God created it in any literal sense and when the term carries with it such a baggage of hierarchy, ownership and externality. So let us be open to a new creation, a new theopoetics. Rethought, restaged, reimagined, radical. One in which humans are part of nature, living within not upon our environment. One where the sacred can be found in the secular, and the most exalted in the humblest.