Today in the church calendar is Palm Sunday, when we remember the story of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem, to a joyous acclamation of the crowd. Whether we grew up hearing the story in Sunday School, or have only heard it more recently, it is a dramatic scene which captures the imagination, and we probably hold the key elements in our minds. Jesus rides a donkey which he has directed his disciples to borrow from strangers; it’s a triumphal entry; the crowds present in Jerusalem for the Passover feast shout ‘Hosanna!’, lay their cloaks on the route and wave palm leaves. The “triumphal entry” is a pivotal moment in all the accounts of Jesus’ ministry, one in which we share the crowd’s hope and elation, but in the knowledge as listeners of what is to come next. What can I add to this that you haven’t heard many times over?

Context is to me absolutely fundamental to appropriate interpretation of the bible, and I am frequently frustrated by the lectionary skipping awkward passages adjacent to the day’s readings, or missing out a chunk in the middle to shorten the story. Even worse is the use of short bible extracts to develop a theme out of context – as a friend put it, “using them as hooks on which the preacher can hang anything they like” (thankfully not common practice in this church!). And yet in today’s reading the author of Matthew’s gospel does exactly that! Twice!!…. Or does he? Is it just our lack of appropriate context to understand that it was not just individual verses that mattered?

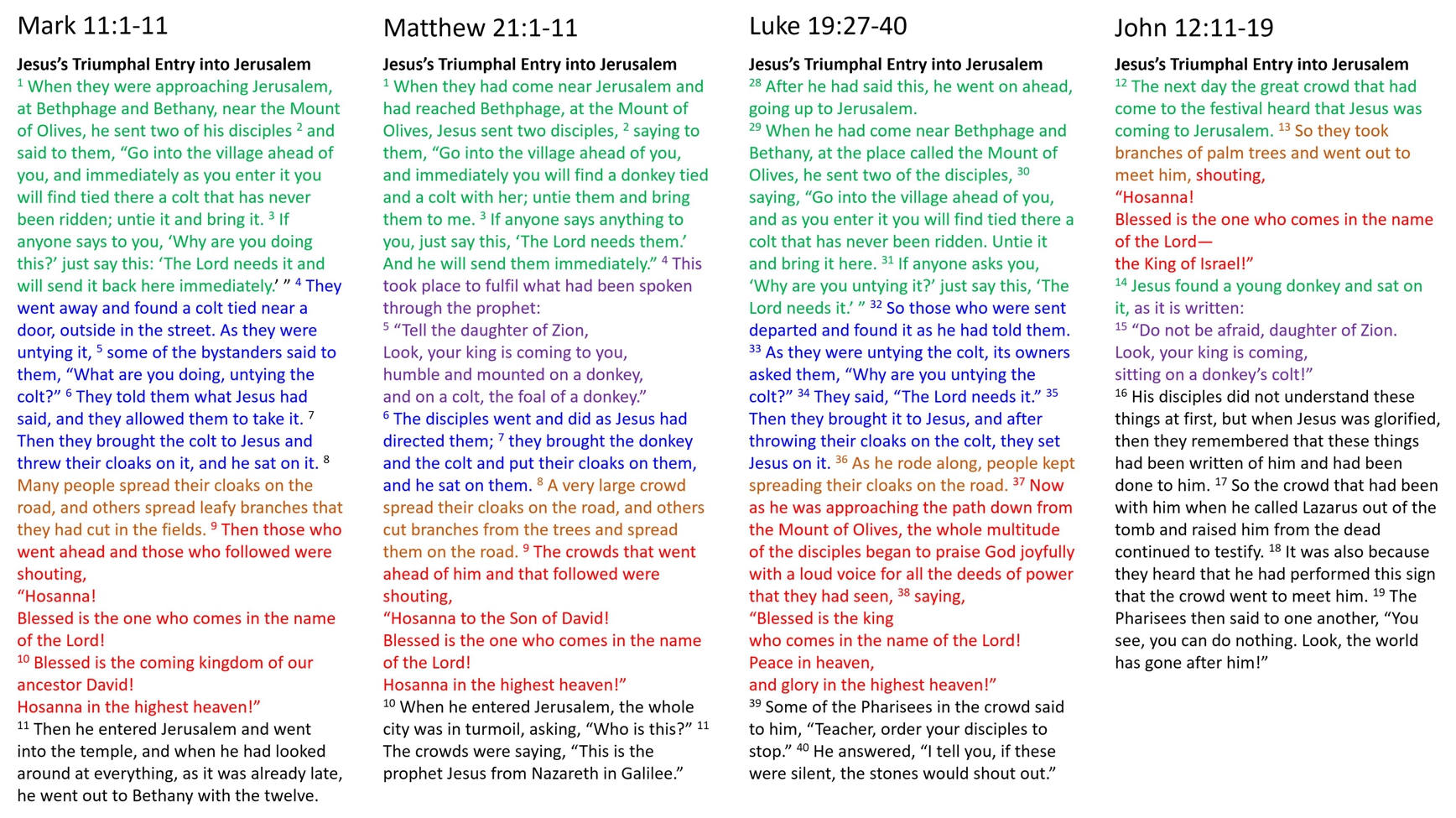

One of the ways I like to get context for the gospel readings is to compare all four versions. Mark’s story is generally the simplest. Scholars such as Joanna Dewey are clear that Mark’s Gospel was a written version of an oral story telling tradition, and in that context the story has to be succinct and dramatic. Although simple, the structure has to be carefully crafted in order to be memorable. There are essential components which have to passed on, but they are linked by the story-teller’s skill. Matthew and Luke, although written later, still belong to an era when only a tiny proportion of the population was literate and so the writing was still intended to be listened to rather than pored over in minute detail as we can now do in our modern typographically saturated world. They show distinctive structural forms which relate to the rhetorical style of the Greco-Roman world, where careful construction and illustration by reference to other texts was intended to convince and persuade. You can very often see the elaborations to Mark’s story which have been applied by Matthew and Luke, and the highly developed theology which is John’s hallmark. Each gospel writer had a particular audience, in a particular place, with particular challenges to face when trying to understand what Jesus’ life, death and resurrection meant in their community.

Like Christmas and Easter, the story of Palm Sunday we know is a conflation of four different gospel accounts plus a bit of background supplied from our Christian traditions. Let’s take a brief look at the gospel accounts.

In the illustration I have colour-coded sections of the text from the four gospels to help see the similarities and differences. You can see straightaway the broad similarity between Mark, Matthew and Luke, but there are differences too. Mark and Luke only talk about a colt – a young male animal, could be a donkey, could be a mule or a horse. Matthew defines it as a donkey and inserts an extract from the prophet Zechariah as a fulfilment of prophecy. In fact Matthew (or a later editor) is so keen to match this prophecy that he describes Jesus riding both and donkey and its foal – a misunderstanding of the poetic nature of the quote. The palm leaves come from John’s description; Mark and Matthew describe leafy branches and cloaks; Luke drops the branches altogether, so to speak – perhaps they were not meaningful in his tradition. A second Old Testament quotation, from Psalm 118, the Hosannas shouted by the crowd, is present in all versions but with subtle variations – “the coming kingdom of our ancestor David” in Mark, “the Son of David” in Matthew, and “the king” in both Luke and John. John’s version has very different order and proportions from the others. He is not interested in where the colt comes from. He does make an imprecise reference to the Zechariah quotation but leaves out the bit about being humble. John makes a great deal of explanation afterwards too, links the crowd to the raising of Lazarus, and has the Pharisees despairing – Jesus is fully in control of his destiny in John’s version.

By comparing the gospels, we can begin to see which parts of the story were important to each of the writers. We can also see this from the way other stories are placed around this one – its context within each gospel. The differences are particularly significant when we compare John’s Gospel with the other three. John’s Gospel is the one which gives us the Passover timing for Jesus’ entry to Jerusalem: Jesus is said to arrive at the home of Lazarus “six days before the Passover” and the crowd welcomes him to Jerusalem “the next day”. In John’s Gospel Jesus travels backwards and forwards between Galilee and Jerusalem over a period of three Passovers. The raising of Lazarus from the dead, which is only described in John’s Gospel, becomes Jesus’ final action before heading into Jerusalem for the last time. Following the entry, John’s story proceeds straight into a series of theological discourses in which Jesus tells of his death, his significance as the light of the world, the true vine, his relationship with God, and so on.

Matthew, Mark, and Luke share a simpler outline of events – a single progression from Jesus’ ministry in Galilee, journeying on through Judea and ending at Jerusalem. A single visit at the end of his ministry in which only one Passover is mentioned, and that not until the events of the last supper. Remember that these gospels were written to be heard, not read, and quite likely heard in one sitting from start to finish (a couple of hours). The author has to use their rhetorical skill to help the audience participate in the story, to identify with the characters.

So, in Matthew’s Gospel the journey through Judea begins to build the tension in the story, from Peter’s declaration that he sees Jesus as “…the Messiah, the Son of the living God.” (16:13), followed by Jesus’ first “foretelling of his death and resurrection”. As Jesus preaches in Judea, the author intersperses his teaching with two more stories of Jesus “foretelling” his death. After the first, Peter is reproved by Jesus for saying it must not happen; after the second, the disciples are “distressed”; and after the third, which is just before his entry to Jerusalem, James and John say they will accompany him to his death. You see the skill of the story telling? There is then a short interlude, as Jesus gives sight to two blind men (in Mark’s version, blind Bartimaeus). But even this has significance. It is a repetition of a story much earlier in Jesus’ ministry (Mt9:28) but in the earlier story, Jesus tells them to keep silent about the healing; this time they follow him. The secret is out, Jesus’ ministry is no longer something to be kept quiet; he has publicly declared his hand.

Now comes the triumphal entry to Jerusalem, and we are swept up with the excitement of the crowd. This is a call to participate! But to participate in what? To join the crowds in praising Jesus as the Messiah? To join a peaceful revolution opposing rule by greed and violence? To throw out the old law-based Judaism and replace it with something new? This is where context is so critical, and the answer may be that the four gospels each had their own agenda. The differences we see reflect differences in the social-historical context of the original audience for the story. Matthew’s gospel was written for a thoroughly Jewish community, probably in northern Galilee, although the written form may have been compiled further north in Syria. There was a growing rift between those who believe that Jesus was the Messiah and those who did not, and the author is keen to use scriptural references to establish Jesus’ credentials in this respect – both to give his community reassurance and to use in debate with the growing Pharisaic movement which came to dominate Judaism after the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. It is in this setting that Matthew is keen to describe Jesus in very Jewish terms – he is explicitly a “Davidic messiah”, there are multiple parallels with Moses, from the Christmas story to the teachings of Torah in the Sermon on the Mount, and he stands for righteousness (proper rather than hypocritical observance of Torah). All backed up by references to the Old Testament.

So, to return to where I started. What is the context for this passage from Zechariah? The book of Zechariah was written late on in the period of exile to Babylon, when the Babylonians had been defeated by the Persians and the new regional superpower took a more progressive approach to local politics, encouraging the rebuilding of the Temple in Jerusalem to support a compliant local leadership. There are parallels there with Jesus’ time – in their recent history the Maccabees, Jewish rebels, had gained freedom from the Seleucid Empire and re-dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem, with a Roman alliance assisting them politically. The writings in Zechariah were intended to encourage the Jewish people, to offer them hope. In the religious understanding of the day, defeat and exile showed that God was against them because they had angered Him (and I think in this case God is definitely a Him with a capital H!); rebuilding of the Temple was interpreted as a return to God’s favour. But in Zechariah the king comes to Zion riding on a donkey because the battle is being won. The preceding and subsequent verses tell of the surrounding nations being destroyed by “the LORD” so that Judah and its capital Jerusalem will be restored. Did the author of Matthew’s gospel intend this as dramatic irony, as the audience knows that the battle is not yet won? Or was he encouraging his listeners to believe that God’s victory portrayed in Zechariah was just around the corner despite the destruction of the Temple? Or were the words simply taken out of context?

The second Old Testament reference used by Matthew is the crowd calling “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest heaven!” Matthew 21:9 is an oblique reference to Psalm 118 (vs 25-26), our first reading today. The Hebrew word hosha’na, transliterated as Hosanna in English, is an appeal, “save us!”, and that is how it is translated in the Psalm (vs 25). Eliezer Segal, Professor of Religious Studies at University of Calgary, says that Jewish readers would recognise the crowd’s call from the festival of Sukkot, not Passover, when Jews wave branches (palms or willow) and circle the synagogue reciting prayers with the repeated hosha’na, (save us!) as they “ask God for bounteous and rain-filled year and for a speedy national redemption”. And how is the festival of Sukkot is associated with national redemption? Through our old friend Zechariah, Chapter 14, in which after the nations have been brought low by the LORD, “All who survive of all those nations that came up against Jerusalem shall make a pilgrimage year by year to bow low to the King YHWH of Hosts and to observe the Feast of Booths.” (Zech 14:16). By placing the “cleansing of the Temple” episode immediately after this Matthew (and Mark) may have been alluding to the final verse from Zechariah 14: “And there shall no longer be traders in the house of the LORD of hosts on that day.”

Which is the key message of Palm Sunday? – that Jesus’ arrival is as a new king, or that Jesus’ arrival is peaceful? Marcus Borg and Dominic Crossan have argued that Jesus’ entry on a donkey is a call to peace, set against the Roman army arriving with war horses to quell any potential for rebellion. I worry that this is a very modern interpretation which assumes Matthew took the passage from Zechariah totally out of context. In Mark and Matthew’s account the triumphal entry is followed by Jesus storming through the temple overthrowing tables and driving out the traders – the only description we have of Jesus displaying physical violence – and by the cursing of a fig tree causing it to wither. Adding that to the implied references to Zechariah 14, and I don’t think Matthew was unaware of the rest of that prophet’s writing.

I have nothing against modern interpretation. I am grateful for scholars who do not think we should remain fixed in a 1st Century understanding of the world! But I do think we must also acknowledge our past and not try to re-write it – we need to acknowledge the wrongs of our Christian heritage as much as the wrongs of our colonial past, of slavery, and of each and every war. If we do not, then we risk not acknowledging how much our current views and situations are shaped by these past events, and we risk perpetuating the wrongs, albeit through inherited rather than active prejudice.

We need to be prepared to accept uncertainty, a diversity of understanding. This is difficult in a religion which has placed so much emphasis on faith, certainty and dogma. We can say, yes the church wrongly interpreted the bible, now we understand better what the writers meant to convey. But do we really understand better? In my view, if we are not prepared to consider the significance of the context of the writings, to realise that diversity of opinion is embedded within both Old and New Testaments, we will still be leaning on that crutch of unconscious bias, looking at the world through Christian-tinted glasses. And here is the largest context in which we must set this and all our bible readings, one which was not available to the writers of the gospels, let alone the Old Testament. Our knowledge and understanding of the world which so far exceeds that of the First Century in geographic, scientific and social terms.

Yes, it can be disorientating to deconstruct all that we have been taught in church. Along with the giddy feeling of new discovery, of things making sense, there is a fear that we have nothing solid left to hold onto. But we have to let go in order to truly regain our sight, like the blind men in Matthew’s story, and join the crowd following Jesus.