Our first reading, from Matthew 10, is part of a collection of sayings, collated as Jesus’ instructions and encouragements to sending out his twelve disciples to spread his message in Judea.

I have always found it difficult to remember the difference between disciples and apostles. It’s an example of how words translated from one language to another can lose their original meanings by becoming associated with specific examples – in this case with Jesus’ followers. The words used in the original Greek writings of the gospels and Pauline letters can be translated more simply as “student” (for disciple) and “envoy” (for apostle). Somehow though, the words have just come to mean Jesus’ followers, almost interchangeably.

But when you think about it, this is a significant step in the early development of the Jesus movement. Jesus’ disciples are only described in the Gospels as apostles when they are sent out to spread Jesus’ message more widely. They are no longer just students but envoys, representatives. How would they have felt? Were they ready?

How do we feel about sharing with others the good news we hear at church? Are we still students, still learning, perhaps not sure yet what that good news really is? At what point do we become apostles? If we take the timeframe presented in Matthew, Mark and Luke literally, Jesus’ entire ministry lasted only a year and this passage is only about halfway through the description of that period. Many theologians think that the three-year timeframe in the Gospel of John is more realistic but John has no equivalent story of sending out apostles.

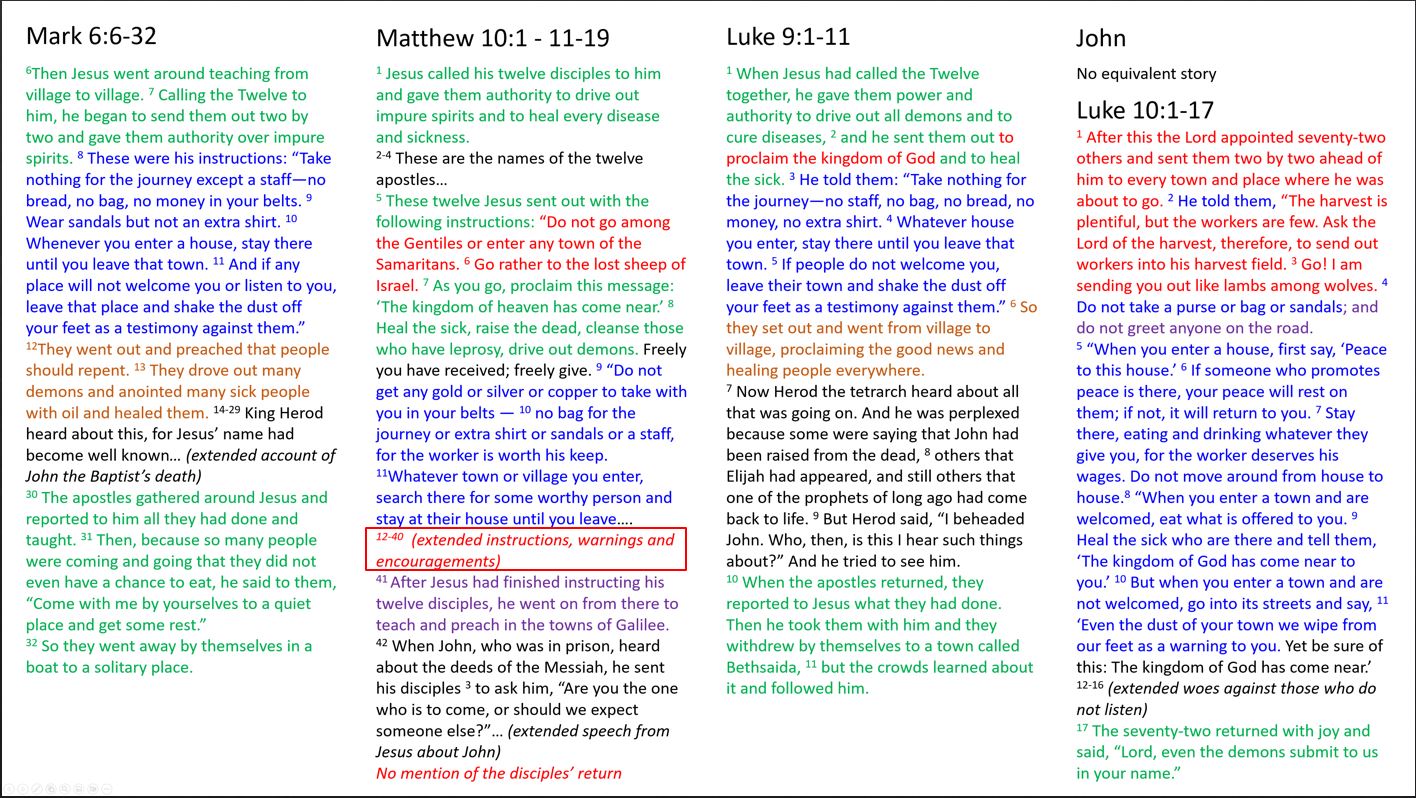

Let’s compare the story of the “sending out of the twelve” in the three synoptic gospels (using the New Revised Standard Version updated edition). Mark’s gospel is the earliest form of the story. It has a simple structure, simple instructions to the apostles, a brief description of their actions. For some reason, Mark includes an extended account of John the Baptist’s death at this point, perhaps indicating continuity of tradition, perhaps showing that now Jesus’ message is impacting more than John’s. When the apostles return, they tell Jesus all they have done. His reaction? – you need a rest and something to eat!

Luke’s version is very similar, with the added mention of proclaiming “the kingdom of God” and leaving out the account of John the Baptist’s death. But less than a chapter later, Luke tells an additional story, not found elsewhere, of Jesus sending out a much larger number of apostles (70 or 72, depending on which 4th Century text is used in translation).

Matthew takes the story from Mark and develops it into a much longer section. Matthew seems to be more concerned to establish Jesus’ relationship with John (who is not yet dead in this version) and adds the names of the twelve apostles. By incorporating elements from a second source, the collection of sayings known as Q, and a variety of sayings from elsewhere in Mark, he weaves a lengthy discourse about the apostles’ mission. Luke includes some of these sayings in Jesus’ address to the seventy-two. The themes of these sayings include reliance on providence for all their needs, appropriate hospitality, and how to deal with hostile treatment, rejection and persecution. This is the section we had in today’s reading, and in it the author goes well beyond the likely experiences of the disciples in Jesus’ own lifetime. Although Matthew gives no description of the apostles’ experience, the other two Gospels report only positive results. The combination of lineage, naming the apostles, and describing the persecutions they must face allows Matthew to establish the authority of the apostles in the difficult times experienced by Matthew’s audience, some 50-60 years later.

These late First Century listeners lived in a period following the fall of Jerusalem and during recriminations between and increasing persecution of Jews. The most peculiar section of today’s reading, the suggestion that Jesus came “to bring not peace but a sword” is a description of their experiences, of the bitter divisions during and following the armed uprising by some Jewish (Zealot) factions and their utter defeat by the Romans. It is inconceivable, when considering other statements from Jesus in Matthew (eg “Love your enemies and pray for your persecutors) that this was intended to be taken literally.

The reference to family feuds is based on a quote from the prophet Micah (7:5-6), whose words must have meant much to the survivors. The words are bracketed by Micah 7:2 “The faithful have been swept from the land; not one upright person remains.”, and Micah 7:8 “Do not gloat over me, my enemy! Though I have fallen, I will rise.”)

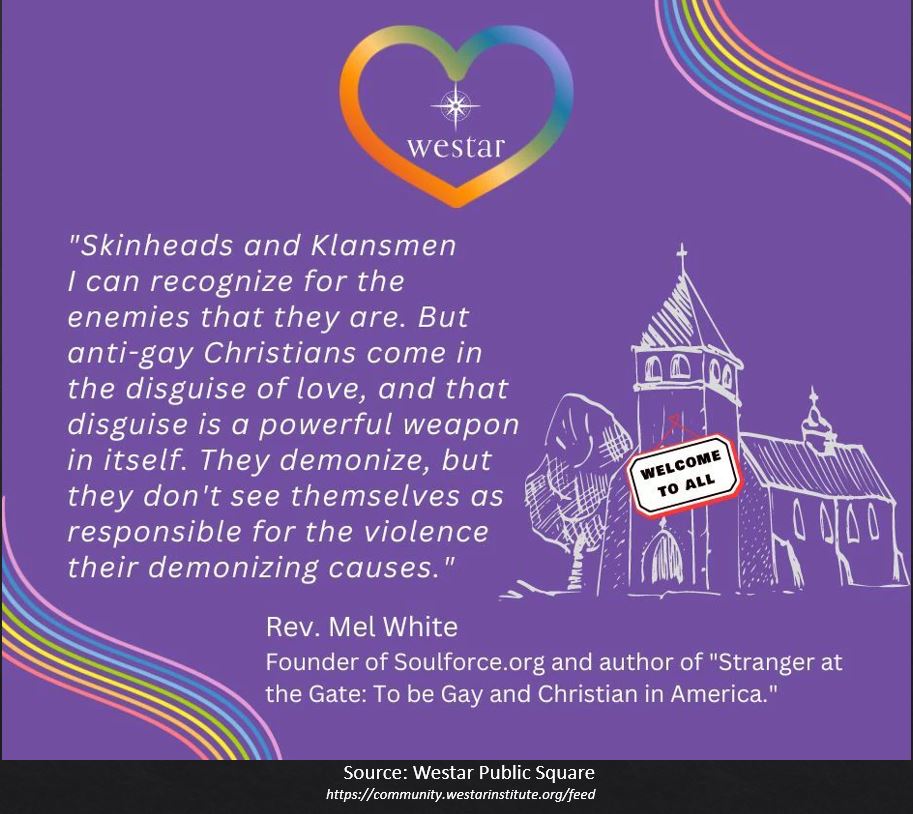

If we don’t understand how the gospels were compiled and the audience they were compiled for, we can make the wrong assumptions about the authenticity and purpose of individual sayings. Phrases taken out of context can be used and abused. Even if we do not take these stories as instructions, there is danger even in assuming they are Jesus’ own words – we can become complacent and use them as an excuse. “Oh, well, if they don’t listen to (my version) of God’s word then they are lost and that’s just how Jesus said it would be”.

And so to the subject of the second reading – sin! Such an easy topic to create division within families and communities, and so easy to take refuge in “I am right and you are wrong”.

The letters of Paul provide many insights and, in bite-sized pieces provide phrases that trip off the tongue easily and have great significance in the Christian church, but try reading more than a paragraph or two and Paul seems to tie the reader (and sometimes himself) up in knots. Part of the problem is the historical filter through which we read Paul, unconsciously reading later Christian interpretations from theologians as significant as Augustine and Luther. There are almost as many interpretations of Paul as there are theologians!

I have been reading two books recently which have helped me to get a new understanding of the man and his letters. Dewey and others, in their re-translation from Greek, “The Authentic Letters of Paul”, suggest that the letters were from the outset, “complex transmissions of a complicated man addressing a variety of issues for some fledgling communities of Jesus the Anointed.”(AD et al) Brandon Scott, in his 2015 reinterpretation, includes an excellent summary of how scholarship has changed our understanding of Paul, particularly since the Second World War confronted Christian theologians with the antisemitism that had been derived in a large part from early Christian interpretations of Paul’s letters.

Paul was not a professional theologian writing a treatise; he thought on his feet and used the Greek rhetorical style and tools of the day to get his point across. Paul was not a Christian, converted from Judaism; he was a zealous Pharisaic Jew who had experienced a revelation, a prophetic calling, but he remained proudly Jewish. He was not writing to all the world, but to individual small communities trying to work out what this revelation meant in practical terms.

In contrast to our reading from Matthew 10, where Jesus sends out the twelve to be apostles (envoys) only to the lost sheep of Israel, Paul describes himself as apostle to “the Nations” (variously translated or referred to as Gentiles, Pagans, or the uncircumcised) – Gal 1:15-16, 2:7-8.

So, Paul saw himself as an apostle. But whose disciple (student) was he? Paul never met the physical Jesus and, according to his own letters (contrary to the story in Acts), after his revelation he did not go to Jerusalem for three years, and then only for fifteen days and only speaking with Peter and James, not the other apostles (Gal 1:17-19). Paul goes on to say that after his second visit to Jerusalem, fourteen years later, the apostles has nothing to add to his own message.

Whose disciple was Paul? We don’t really know but, in his letter to the Philippians, Paul talks of his Pharisaic view of the law and his zeal for persecuting the early Jesus community. NT Wright makes a good case for Paul originating as a hardline Shammaite Pharisee, “what we would today call a militant right winger” (TW). Paul’s pharisaic understanding shaped two aspects of his later mission to the Nations.

First, his view of the end-times which would be heralded by God’s Messiah included the belief that all the nations would be brought to Jerusalem to worship God.

A second assumption from Paul’s pharisaic discipleship was this: “the nations” were by definition idolators worshipping false gods, and what went with idolatry in their view? All kinds of immorality and debauchery! In Paul’s Jewish understanding, the nations had disobeyed God and deserved God’s punishment.

Paul’s radical new insight, which came from his revelation, was that just as God had accepted Abraham’s expression of faith (in the horrific near sacrifice of his son, Isaac) and made a covenant with the Jewish people, so God had now accepted Jesus’ expression of faith in going to the cross. It was the faith of, the faithfulness of, not faith in Jesus that was critical (BBS), and that faith had been accepted by God as a ransom to redeem the nations.

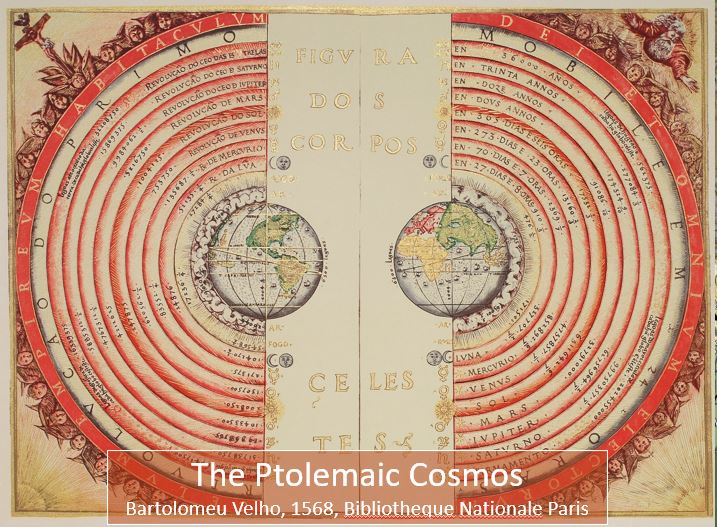

As a Greek speaking Jew, from Tarsus according to Acts (in what is now southern Turkey), Paul would also have been a disciple, perhaps unwittingly, of Greek philosophy. When Alexander the Great established an empire stretching from Macedonian Greece to Egypt in the late 4th Century BCE, the cultural interaction resulted in Hellenistic Judaism. This combination of Jewish religious tradition with elements of Greek culture and philosophy gave rise to the Septuagint, the Greek translation of the Hebrew bible used by many of the New Testament authors, and to Jewish philosophical writers such as Philo of Alexandria. Just as the Septuagint translation would have influenced Paul’s religious views, Greek philosophy and astronomy would have defined the shape of the cosmos, as it did for another 1500 years until Copernicus!

The scholar of Judaism and early Christianity, Paula Fredriksen, describes this world view. The architecture of the Hellenistic cosmos encoded moral value. What was ‘up’ was ‘good’: ‘better’ both metaphysically and morally than what was ‘down’. And look what is drawn above the highest ring of the cosmos in Bartholomeu Velho’s 1568 diagram: God, Jesus and the angels peer down at the earth. According to Philo of Alexandria, an elder contemporary of Paul’s, the heavenly firmament was “the most holy dwelling-place of the manifest and visible gods”. Like the universe, the human being was seen as a composite of higher and lower aspects: a fleshly body animated by a lower soul, which humans shared with animals; and a higher part of soul, the vessel of “spirit” or “mind”. The lower, nonrational parts of the human soul was subject to passion that joined spirit to physical flesh (PF).

In the letter to the Romans, Paul writes with the intention of visiting Rome on his way to new mission territory in Spain, and his intention is to gain their support for his mission. To do so, he writes in an elegant and formal rhetorical style which would be readily understood by educated listeners, listeners who were immersed in this Hellenistic world view.

When Paul uses the Greek word which is normally translated as “sin”, he is trying to convey a much more pervasive character than the individual actions we tend to use the word sin for. He sees the world as full of spiritual forces and the translation used in Dewey et al is “the seductive power of corruption”. This phrase ties in the association of sin and death – in a Hellenistic world view the very fact that we are mortal was an indication that we are imperfect, in contrast to the eternal heavens above.

Much of the Christian church is still caught up in the inherited world view in which the divine realm is perfect and flesh is a corrupt form, a pale imitation; where perfection is eternal, and mortal humans are therefore imperfect, sinful. We don’t believe in the cosmic model, why do we believe in the human version of it?

Paul’s gospel is that God’s acceptance of the crucified Jesus means God’s favour is now bestowed on the Jews and the nations alike. All are now considered children (sons in his terminology) – the Jews through birth, and the nations through adoption. This adoption is symbolised in the ritual of baptism, which is described in today’s reading. The literal translation of the Greek word is to dunk, to be immersed under water. Paul uses the analogy of immersion as ritualising death, in this case Jesus’ death. “How is one brought back to life? Through breath, breathing, gasping for air.” Elsewhere in his letters (eg 1Cor 12:3), Paul speaks of the spirit, a translation of the Greek word, “pneuma” from which we get pneumatic, which literally means wind or breath and is used as a metaphor for God’s activity or presence. So having died in the ritual act of baptism, one breathes life back in, the spirit of God. (BBS).

A friend and former colleague who had a Thai wife once told me that Buddhism made more sense to him than Christianity. He said the Christian idea of forgiveness did not fit with human nature – if people were forgiven why would they need to change their behaviour, to behave better? If I have known my bible better in those days I would have pointed out that was a big part of what Paul was tackling in his letter to the community in Rome. Paul anticipates this question from his listeners. Here we have another Greek concept: self-mastery. Self-mastery in Greco-Roman understanding is learned behaviour, taught from an early age, defined by the law for the orderly conduct of society. To rule others, the elite must control their own passions.

I think the church can still tend towards the idea that sins come from a failure to rule our emotions, that the body is separate from and controlled by the mind. Modern science and medicine does not fully endorse this separation. Yes, emotions can sometimes control our thinking. For example, when we are angry the body prepares for fight or flight and we lose some capacity for rational thought (planning ahead, negotiating). But, as the farm mental health activist, Elle Perriam of Will to Live, points out: “your mind and body are directly connected. How you eat, drink, move, rest, recover, who you interact with daily and even what you say to yourself – the inner dialogue – are important in achieving our health outcomes.”

Paul’s readers, who were members of the nations, were tempted to see Jesus as a teacher of the Jewish Law as a way of self-mastery, as Philo of Alexandria did. (BBS). But in Paul’s view, this missed the point: the Jewish Law only applied to the Jews; the nations had been reconciled with God through an act of God’s grace. They had no excuse not to respond to God as loving children to a loving parent; the Jewish Law would only create new barriers.

The modern Christian church still tends to get hung up on this issue. If we stick unquestioningly to following codes of conduct defined for a very different time and social setting, we are falling into the same trap that Paul was addressing in his letter to the Romans – creating excuses, and barriers to our relationship with God. Our known world is so much bigger than Paul’s; our social and trading relationships extend to people across the globe, we have greater understanding of the interdependence between nations, and between humans and nature; there are so many more issues to deal with. Modern sin, the modern “seductive power of corruption” could be seen as our failure to address climate change, wealth inequality, the refugee crisis etc. These are much more significant than breaches of personal codes of conduct. We may say, this is beyond our control, but in democracies we can choose whether to use our vote to tackle issues of global significance or to enforce insular religious codes of conduct. And in our personal behaviour and the example we set as apostles, we can behave as loving children of a loving God.

References:

AD et al – Dewey, Arthur J et al, 2010. The Authentic Letters of Paul

BBS – Scott, Bernard Brandon, 2015. The Real Paul: Recovering His Radical Challenge

PF – Fredriksen, Paula, 2012. Sin: The Early History of an Idea

TW – Wright, Tom, 1997. What St Paul Really Said