How do you feel when you read or listen to the news these days? There are so many problems in the world: climate change and environmental destruction, children starving while warlords battle, people making long, dangerous migrations to escape persecution or simply to find a basic quality of life. Thousands killed, buildings and infrastructure turned to rubble and billions of dollars spent on weapons, for what? Temporary control of small areas of land at the cost of a perpetuity of enmity and bitterness. Even as Daniela pointed out a few weeks ago, when New Zealand seems to be far from the rest of the world and the biggest news is the price of a free lunch (and its quality), it can still seem that we are in a hopeless state where value is measured only in dollars and founding documents could be re-written by referendum. Do you feel like despairing?

Despair, or lament? I think there is a difference. We heard in the second half of the Psalm today, fear of defeat but enduring hope. “Lament is an act of protest as the lamenter is allowed to express indignation and even outrage about the experience of suffering”, writes Soong-Chan Rah in his 2015 book, Prophetic Lament: A Call for Justice in Troubled Times. “Lament is honesty before God and each other”. Lament is strongly expressed in the bible. It is not surprising – biblical Israel was a tiny nation wedged between competing large empires. Little more than a buffer state, but a buffer state with big ideas of its place in the world, big ideas about the faithfulness of their God.

We can often find our moods reflected in the bible. One of the reasons the bible has spoken so strongly to people over the ages, along with other religious texts, is that it displays the whole gamut of human emotions. If you are feeling joyful or depressed, confident or fearful, angry or sad you can find these feelings put into words, often better than we can do so ourselves. We have heard how the Psalmist expressed two moods in today’s reading – confidence and fear. Does the reading from the Gospel of Luke express emotions to you? Or do writings about Jesus have to be viewed in a different light from the Psalms? Do we view them as the experiences of a divine figure, or even an extraordinary human figure, unrelatable to our own experiences and emotions?

We need to be careful how we read the gospel stories as Christians. We have a tendency to bring in assumptions both from elsewhere in the bible and from later theological interpretations. We unconsciously merge descriptions of Jesus’s life, death and after-death from the different gospel accounts, from the portrayal of the early church in the Acts of the Apostles, and from the letters written by Paul and others. When words are written as spoken by Jesus, parables, wisdom sayings and prophetic calls we often interpret them through the lens of later Christologies. And as for the book of Revelation, the merging of the Christ of the apocalypse with Jesus of Nazareth is an alarming and dangerous development in modern Christianity.

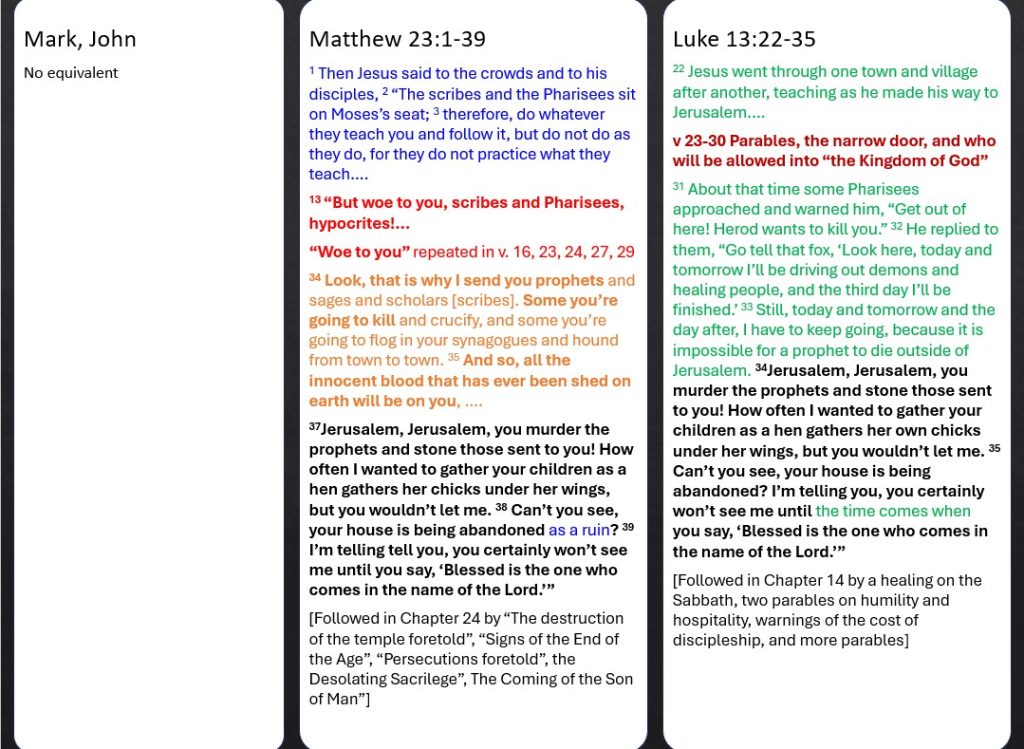

Let’s step back from the lectionary selection from Luke and compare it with versions found in the other gospels. Since we have after all four different accounts of Jesus, we might as well use them! The words of the lament for Jerusalem are found in both the gospels according to Luke and Matthew, but not those of Mark or John. You can see the wording is almost identical in Luke and Matthew. The close correspondence of wording in the original Greek implies that both used the same written, not oral, source. I’ll come back to that shortly.

Each gospel writer addressed a different audience at a different time and had a different understanding of the ministry and person of Jesus. The way they placed acts and sayings within the narrative affects how the words are read or heard. If we compare how today’s reading is placed within each gospel, we see that the two authors put the lament for Jerusalem in very different places. While both use the same broad narrative outline from the Gospel of Mark, Luke has placed the text within a long narrative of Jesus’ travel from Galilee to Jerusalem. Matthew, on the other hand includes the text as part of Jesus’ preaching after he has arrived in Jerusalem.

Now let’s take a closer look at the context of the reading to see what is adjacent to the reading in the text. The gospels were carefully crafted to deliver a message, not written as journalistic accounts. Looking at the texts surrounding the lament, there are other differences between the gospels of Luke and Matthew. Luke precedes it with a series of short parables about the difficulty of entering the Kingdom of God, which are found elsewhere in Matthew. Then Luke adds a rather surprising conversation with Pharisees who are not plotting to kill him but warning him to avoid an early death at the hands of the Roman-backed ruler of Galilee, Herod Antipas (v 31-33). This conversation has no equivalent in the other gospels. Jesus dismisses Herod and turns away towards Jerusalem.

Now let’s take a closer look at the context of the reading to see what is adjacent to the reading in the text. The gospels were carefully crafted to deliver a message, not written as journalistic accounts. Looking at the texts surrounding the lament, there are other differences between the gospels of Luke and Matthew. Luke precedes it with a series of short parables about the difficulty of entering the Kingdom of God, which are found elsewhere in Matthew. Then Luke adds a rather surprising conversation with Pharisees who are not plotting to kill him but warning him to avoid an early death at the hands of the Roman-backed ruler of Galilee, Herod Antipas (v 31-33). This conversation has no equivalent in the other gospels. Jesus dismisses Herod and turns away towards Jerusalem.

The result of this structure in Luke is that Jesus appears in control of his destiny: predicting his death and calling Jerusalem to repentance so that he, Jesus, can demonstrate God’s love of His people Israel. I feel the dominant mood is one of assuredness and acceptance of the future. There is also sorrow for the unrepentant (those who have difficulty entering the kingdom) and even perhaps a touch of triumphalism, as the last sentence can be read as a prediction of Jesus’ entry to Jerusalem on Palm Sunday. For the author of the Luke-Acts two volume book, the Holy Spirit drives the plot, the move from Galilee to Jerusalem is part of the big plan, and the focus is on Jerusalem where Jesus will be crucified and resurrected and where the church will be born at Pentecost.

Not so for Matthew, who has a focus on Galilee both in Jesus’ ministry and his resurrection. For Matthew, Jerusalem is associated with death: Jesus’ crucifixion and the temple’s destruction. Galilee is where Jesus spends most of his ministry and Galilee is where he returns after the resurrection. Matthew precedes the lament for Jerusalem by a series of verbal assaults on the Pharisees and scribes, “woe to you…” and accompanies it with apocalyptic predictions of the destruction of the temple and the end of the age. The mood evoked by Matthew is one of frustration, rage even, at hard-hearted, pettifogging interpreters of the law. Michael L White suggests Matthew’s portrayal of Jesus is as “the righteous teacher of Torah” and that it was written at a time when the Jesus movement was facing criticism from the Pharisaic movement which was emerging as the new religious leadership in the last decades of the first century.

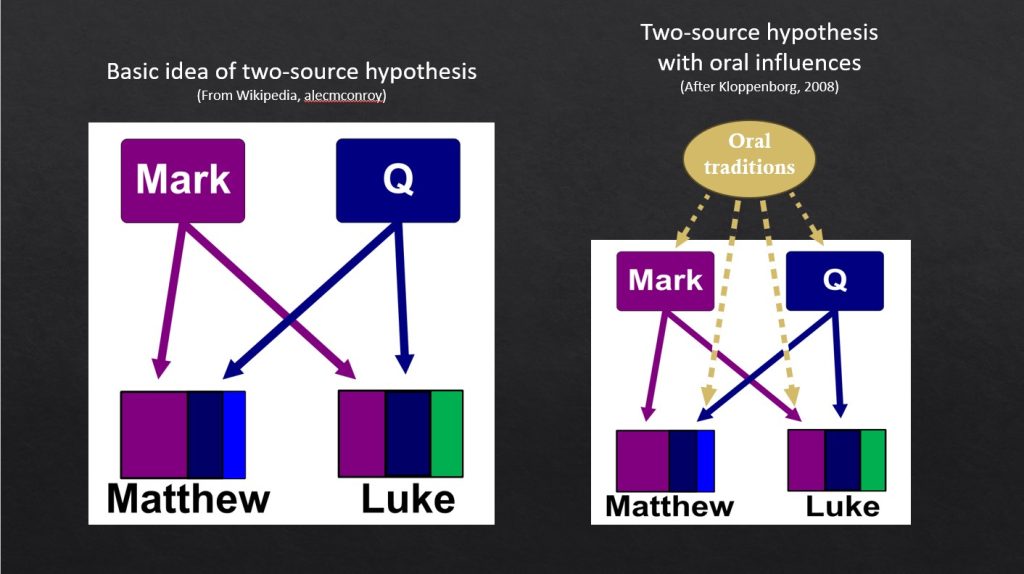

So how did two such different gospel accounts, written in different times and places come to have such similar texts? The idea that Matthew and Luke both used Mark’s gospel and a second common source was proposed as early as 1838 (Christian Weisse). Alternative explanations were proposed, such as Luke having a copy of Matthew’s gospel to use when writing his own, but consensus developed around the two-source model. We call the second source, “Q”, from the German word “quelle”, meaning simply “source”. Q is also sometimes called “the sayings gospel” because it is a collection of sayings without a narrative structure. No copy of the original has been found, so the gospel has to be reconstructed from Matthew and Luke. Perhaps the community which compiled it lacked resources to re-copy and distribute it, perhaps the Q gospel never reached arid climates such as Egypt where the fragile documents would not decay.

So how did two such different gospel accounts, written in different times and places come to have such similar texts? The idea that Matthew and Luke both used Mark’s gospel and a second common source was proposed as early as 1838 (Christian Weisse). Alternative explanations were proposed, such as Luke having a copy of Matthew’s gospel to use when writing his own, but consensus developed around the two-source model. We call the second source, “Q”, from the German word “quelle”, meaning simply “source”. Q is also sometimes called “the sayings gospel” because it is a collection of sayings without a narrative structure. No copy of the original has been found, so the gospel has to be reconstructed from Matthew and Luke. Perhaps the community which compiled it lacked resources to re-copy and distribute it, perhaps the Q gospel never reached arid climates such as Egypt where the fragile documents would not decay.

In 1985 a group of scholars began producing a collaborative reconstruction of Q which collected the previous 150 years of scholarship on Q and deciding each “variant” through an extended process of data collection, debate, and editorial decision. The text of Q published by the International Q Project (IQP) in 2000 offers a reconstructed gospel of about 4,500 words or about 260 verses, about a quarter of those in Matthew and Luke. Two key contributors to the work have subsequently published books introducing the results of the seminar to a wider audience: Burton Mack and John Kloppenborg present clear explanations of the process of reconstructing the text, and a picture of the Jesus community which originally preserved the sayings.

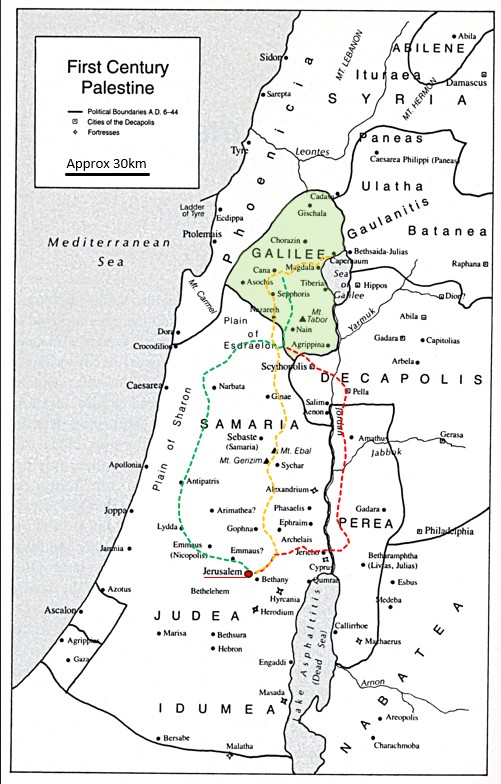

So, who were the people of Q? Kloppenborg tells us their world was a Jewish (or “Judean”) world, with no debate about whether Jewish laws should be kept (such as Mark’s reference to the Sabbath, or Luke’s to table practices) and very few Gentiles make an appearance. Unlike the urban audiences of Matthew and Luke, the Jesus movement reflected in Q was a rural community. The text is replete with agricultural and rural metaphors: olive, fig and fruit trees, sowing, harvest and day labourers, the rapid growth of weeds, the requisitioning of labourers or farm animals by the military, housebuilding in wadis where flash floods can destroy the house, shepherding and work in the fields. Geographical references in Q – small towns and villages: Capernaum, Bethsaida, Khorazin and Nazara – place the text’s origins in Galilee, the location of Jesus’ early ministry according to all the gospel accounts.

Rural Galilee is a long way north of Jerusalem – it is about 120km from Capernaum to Jerusalem as the crow flies, and more like 160 as the donkey walks – and separated from its southern cousins in Judea by the difficult and dangerous terrain of Samaria. Galileans were renowned for being fiercely independent. Burton Mack suggests that we think of it as being part of Israel because it was included in the kingdoms of David and Solomon, but they only lasted less than 100 years! More recently, Galilee had only been annexed by Judean expansion a little over 35 years before Pompey turned Palestine into a Roman Province. Why then does Jerusalem make an appearance in Q? It does so only twice. First, in the story of the temptation of Jesus, when the devil takes Jesus to Jerusalem and tempts him to throw himself off the top of the temple. Although distant, the temple was part of 1st Century Jewish religious identity, and therefore of Galilean identity since there was no real distinction between religion, national state and daily life.

The only other reference to Jerusalem is in today’s reading, and there are two elements likely to have contributed to its inclusion in Q. First, Kloppenborg suggests the people of Q saw Jesus’ death as inextricably linked to his identity and activity as a prophet. They took a view of Israel’s history as “a repetitive cycle of sinfulness, prophetic calls to repentance (which are ignored), punishment by God, and renewed calls to repentance with threats of judgement”. This links with the second element. Burton Mack interprets the lament for Jerusalem as a late addition to the text, made in direct response to the destruction of the temple during the Roman-Jewish war from 66-73 CE which could be interpreted as part of that prophetic cycle.

Burton Mack interprets the social history of the region played out in the writings of Q. The earliest Q sayings are addressed to the ordinary (peasant) people. Jesus speaks wisdom in parables and short sayings, addressing the complexities and ironies of everyday life, encouraging people to think about what really matters. This includes the content of Matthew’s ‘Sermon on the Mount’ (Luke’s ‘Sermon on the Plain’) – teachings such as ‘love your enemies…’, ‘be merciful…’ and how to pray (the ‘Lords Prayer’). Mack suggests that a second layer of text was added as the Q community came up against opposition to their views and way of life. These later sayings and actions are more focused on who is in and who is out. Criticisms of the Pharisees enter the range of sayings, judgements on those who oppose and congratulations and rejoicing for those who recognise the kingdom of God. It is at this stage that a more prophetic voice is heard.

And then came the Roman-Jewish War. Burton Mack writes: ‘Reading the history of the war written by Josephus, one gets the impression that the internecine conflicts within Judea and Jerusalem were as devastating to the social order as the armies of the Romans were to the city walls and defences.’ Simon Montefiore writes that, when Ananus and the priests in Jerusalem started to lose control of the rebels, ‘John of Gischala and his Galilean fighters saw an opportunity to win the entire city… invited in the Idumeans… from the south of Jerusalem… who stormed the Temple, which ‘overflowed with blood’, and then rampaged through the streets. killing 12,000. They murdered Ananus and the priests and desecrated their bodies. “The death of Ananus”, says Josephus, “was the beginning of the destruction of the city”‘.

For the people of Q and indeed all Jewish peoples of the 1st Century, the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem was the end of the world as they knew it. A complete change in world order. The Temple-State had been the standard model of nationhood for centuries. Losing the Temple with its associated rites meant loss of everything familiar, fear for the future. ‘Jerusalem, Jerusalem, you murder the prophets and stone those sent to you!’ (and the priests, we could add!) The text harks back to the book of Lamentations, written after the loss of the first Temple when Jerusalem was sacked by the Babylonians. How could it be that the city that God loved had been destroyed? Does God not care?

An earlier reference in Q to the prophets being killed is portrayed as the voice of Wisdom. Did the people of Q imagine Jesus speaking the words of today’s reading, or the voice of Wisdom, Sophia? Because Q is a collection of sayings, with no narrative and often without any context, it is hard to know. For the people of Q, Jesus started as a messenger of wisdom. As Kloppenborg writes, ‘It is not a dying and rising saviour that we see in Q, but a sage with uncommon wisdom, wisdom that addressed the daily realities of small-town life in Jewish Galilee.’ Looking back at the text, it can be hard to separate the voice of Jesus from the voice of Wisdom.

As we have seen, Matthew and Luke made different decisions on where and how to include elements from the Q gospel in their narrative. By following their own agendas, they lost the original context of the text. A lament about the fall of Jerusalem has become, in Luke, an expression of divine control of history and, in Matthew, an opportunity to portray their later theological opponents, the Pharisees, as the faithless ones bringing retribution upon Jerusalem. Worse, Matthew’s version has subsequently been incorporated into a theme of vilification of the entire Jewish people. Luke’s use of the quotation is less problematic, but his placement implies a prediction of the future rather than a lament for past events, compounding the historical Jesus and the theological Christ.

If we can return the text to its original context in Q, I think we can relate it more to our current situation. For the people of Q, the destruction of the Temple meant a change in world order, with all the associated fear and uncertainty. ‘Jerusalem, Jerusalem’ was a lamentation for ongoing suffering. ‘Jerusalem, Jerusalem…’ or we might say today, ‘Gaza, Gaza…’, ‘Kyiv, Kyiv…’, ‘America, America…’

Soong Chan Rah suggests that our western culture and church are uncomfortable with pain and suffering, but that ‘the human attempt to diffuse and minimize the emotional response of lament… only adds to the suffering.’ ‘The appropriate response would be to express presence and … lament alongside the sufferer rather than explain away the suffering.’ When a community does not recognize that segments of its community are in pain, it does not recognise the need for a message of hope. If it does not recognise the need to lament, it does not recognise the need to change. I would add that if we recognise lament in its proper context, it will neither lead to blaming others unjustly nor waiting vainly for divine intervention to fix the problem. When we lament, we recognise the pain of the world, we associate ourselves with that pain, and therefore we must respond by doing what we can to relieve that pain. What differentiates lament from despair is hope. And hope must lead to action.

References:

Kloppenborg, John S., Q, the Earliest Gospel: An Introduction to the Original Stories and Sayings of Jesus. Presbyterian Publishing Corporation, 2008.

Mack, Burton L., The Lost Gospel: The Book of Q and Christian Origins, HarperOne, 1993

Montefiore, Simon Sebag, Jerusalem: the Biography, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2011

Rah, Soong-Chan, Prophetic Lament: A Call for Justice in Troubled Times, InterVarsity Press, 2015