There is a common theme in today’s bible readings. Although the writings are separated by at least 600 years, both are stories about the treatment of widows in Israelite communities. This is a common theme in the Hebrew Testament: the book of Exodus contains a strong injunction about the care of widows, orphans and immigrants: “You shall not wrong or oppress a resident alien, for you were aliens in the land of Egypt. You shall not abuse any widow or orphan. If you do abuse them, when they cry out to me, I will surely heed their cry; my wrath will burn, and I will kill you with the sword, and your wives shall become widows and your children orphans”! (Exodus 22:21-24, NRSVue). Not the way we think of God speaking to us in modern times, and strong language even for that iron-age people, when violence was the routine method of control.

In a recent blog post by the Westar Institute, scholar Bernard Brandon Scott writes: “This triad of orphan, widow, and immigrant [translated as “alien” in the NRSV] occurs often in the Hebrew Bible… [and] indicates a persistent problem. The mistreatment of widows, orphans, and immigrants was common, and the problem never solved. These three groups are vulnerable, because they have no protectors in society. If God does not come to their rescue, their situation is desperate.”

When looking at today’s readings I found I could take one of two approaches to my reflection. On the face of it, the story about Ruth can be seen as a model of self-sacrifice – giving up her family, country and culture to support her mother-in-law who was returning to Judah. A role model of faithfulness to family and to the God of Israel. Similarly, the poor widow in Mark’s Gospel, who gives all her money to the temple can be seen as an illustration of how we should behave – living with a generous heart, sacrificing our needs for the benefit of others, dedicating our lives to God.

This is a Christian theme which aligns with the idea that Jesus gave his life as a sacrifice to redeem us, to make things right with God; that God’s son came to earth to die on the cross for us sinners. This is the ‘God of the bridge builders’, from John Caputo’s book “What to Believe?”, that I talked about last time. The God who is out there and up there, whom we can only access by means of elaborate bridges built of elaborate theological constructs. But if we dare take the radical path John Caputo suggests, we find a God who is already among and within us, and this God I find much more aligned with the God of mercy and justice proclaimed by Jewish prophets. This is the God proclaimed by the Jesus who is found by a careful distillation of the Gospels, discarding later theological overprints to find the simple message: God is love, love one another, not as Jesus died but as he lived.

So, without discounting the value of a generous heart, what is the second way of looking at today’s readings? My basis for understanding Ruth is found in John Dominic Crossan’s book, The Power of Parable. Dominic Crossan says that Jesus did not invent the story telling genre of parables – it was already present in the Hebrew Testament. When Matthew 13:34 writes, “Jesus told the crowds all these things in parables; without a parable he told them nothing” he is paraphrasing a quote from Psalm 78:2. The book of Ruth is an example of a book-length parable.

Let’s backtrack just for a moment. What exactly is a parable? To quote Crossan: “A parable… is a metaphor expanded into a story… (Metaphor = carrying something over [meaning] from one thing to another…. seeing something as another). An ordinary story wants you to focus internally on [the story] itself. A parable… always points externally… to some different and much wider referent. Whatever its actual content is, a parable is never about that content.”

With that in mind, the conventional story of Ruth, the faithful daughter-in-law, has another purpose, to which its original listeners were being directed. It is harder for us, because we lack the context to understand the metaphor and need scholars such as Dominic Crossan to explain. Now, although I am often irritated by the way the lectionary skips whole chunks of biblical texts, misses crucial background or sections inconsistent with the desired message (leading the witness, to use a legal term!) today’s extract has most of the essential elements of the parable as Crossan sees it.

Naomi, an Israelite, has returned to Judah and needs to find a husband for her widowed Moabite daughter-in-law, Ruth. Naomi identifies a kinsman of hers, Boaz, as a likely candidate, and sends Ruth to seduce him. Boaz is impressed and, to cut a long story short, they are married and have a child. And that child was the grandfather of David, King of Israel. Ruth, a Moabite, was the great-grandmother of David.

Naomi, an Israelite, has returned to Judah and needs to find a husband for her widowed Moabite daughter-in-law, Ruth. Naomi identifies a kinsman of hers, Boaz, as a likely candidate, and sends Ruth to seduce him. Boaz is impressed and, to cut a long story short, they are married and have a child. And that child was the grandfather of David, King of Israel. Ruth, a Moabite, was the great-grandmother of David.

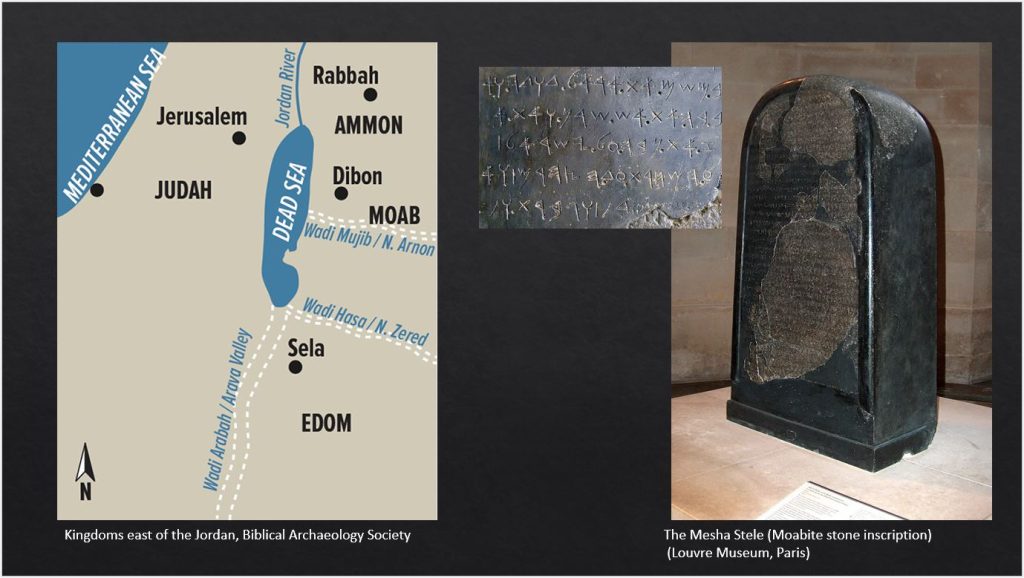

So what, you may ask? To understand the significance of this, we need to know a little history and geography, and some Jewish law. First the history and geography. Moab was east of Judah, on the other side of the Dead Sea, currently part of Jordan. The Israelites (including those in the southern Kingdom of Judah) and the Moabites were enemies through a long period of history. Their battles are recorded from the Israelite point of view in the books of Numbers, Deuteronomy, 2 Kings and Chronicles, as well as passing references in many of the prophets. We also have archaeological confirmation from the other side of the argument. The Mesha Stele, a basalt stone monument from c. 840 BCE, preserves a lengthy text dictated by Mesha, King of Moab. The inscription confirms Moab and Israel as analogous kingdoms in irreconcilable opposition: each with its own territory, people, king, royal lineage and god. Achievements and military successes are ascribed to support from their deity; defeats are seen as the result of their god’s anger with them – sound familiar?

The colourful Jewish myths-of-origin in Genesis suggest a pervasive prejudice, as the kingdoms of Moab and Ammon are described as being the descendants from the incestuous relationship of Lot with his daughters. A law in Deuteronomy (23:3-6) suggests a seriously long-term grudge: 3 “No Ammonite or Moabite shall come into the assembly of the LORD even to the tenth generation. None of their descendants shall come into the assembly of the LORD forever, 4 because they did not meet you with food and water on your journey out of Egypt and because they hired against you Balaam… to curse you…. 6 You shall never promote their welfare or their prosperity as long as you live.” It is this prohibition which lies at the heart of the parable of Ruth.

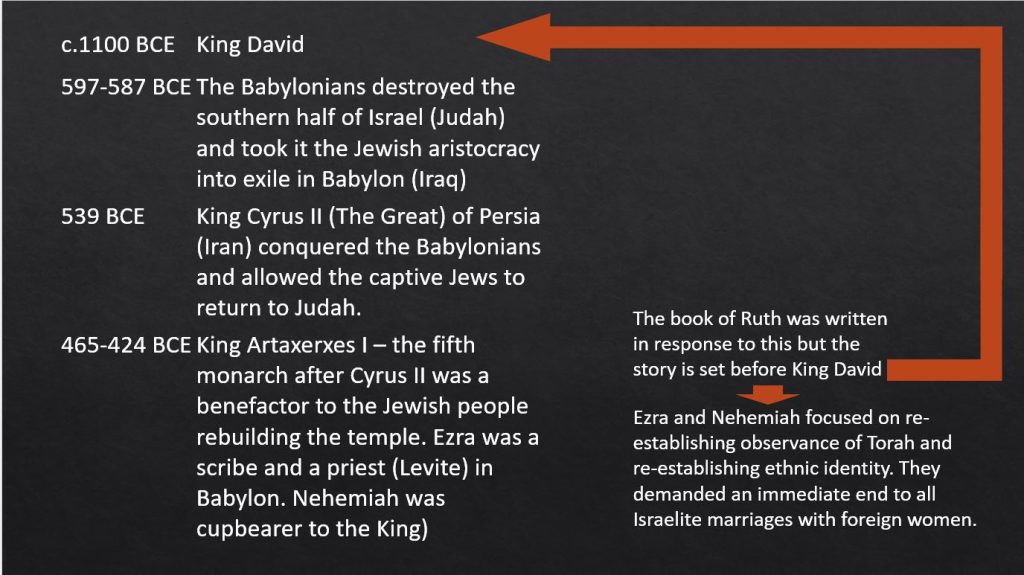

Although the story describes a period of history before King David, the story was actually written long after. Here is the timeline. Around 597-587 BCE the Babylonians destroyed the southern half of Israel (Judah) and took the Jewish aristocracy into exile in Babylon (modern Iraq). In 539 BCE King Cyrus II (The Great) of Persia (modern Iran) conquered the Babylonians. His policy and that of his successors was to establish clients and allies rather than to make perpetual enemies, so he allowed the captive Jews to return to Judah. Between 465-424 BCE King Artaxerxes I, the fifth monarch after Cyrus II, continued this policy and was a benefactor to the Jewish people rebuilding the temple. Ezra was a scribe and a priest in Babylon at that time. Nehemiah was cupbearer to the King. When they returned to Judah and rebuilt Jerusalem, Ezra and Nehemiah focused on re-establishing observance of Torah and ethnic identity. They demanded an immediate end to all Israelite marriages with foreign women. Nehemiah 13:1-3 quotes directly from that Deuteronomic law we heard a moment ago.

Although the story describes a period of history before King David, the story was actually written long after. Here is the timeline. Around 597-587 BCE the Babylonians destroyed the southern half of Israel (Judah) and took the Jewish aristocracy into exile in Babylon (modern Iraq). In 539 BCE King Cyrus II (The Great) of Persia (modern Iran) conquered the Babylonians. His policy and that of his successors was to establish clients and allies rather than to make perpetual enemies, so he allowed the captive Jews to return to Judah. Between 465-424 BCE King Artaxerxes I, the fifth monarch after Cyrus II, continued this policy and was a benefactor to the Jewish people rebuilding the temple. Ezra was a scribe and a priest in Babylon at that time. Nehemiah was cupbearer to the King. When they returned to Judah and rebuilt Jerusalem, Ezra and Nehemiah focused on re-establishing observance of Torah and ethnic identity. They demanded an immediate end to all Israelite marriages with foreign women. Nehemiah 13:1-3 quotes directly from that Deuteronomic law we heard a moment ago.

The story of Ruth was written as a cryptic criticism of these leaders during the restoration of Judah, but its plot is set perhaps 6 or 700 years earlier, before the birth of King David. Whatever the truth of the story, whether or not Naomi, Ruth and Boaz were actually ancestors of King David, the message of the metaphor, the sting in the tale, is this: If what Nehemiah and Ezra were enforcing in the newly re-built Jerusalem was applied in this story Ruth could never have said to Naomi, “Your people shall be my people, and your God my God” (1:16); and Boaz would have had to divorce Ruth and disown her child, who was grandfather to David, “the once and future king” of Israel.

With this context revealed, we can see that the book of Ruth illustrates a clash of laws. Which was the more important law: one providing protection for immigrants and widows, or one preserving ethnic identity? That probably seems straightforward to you, but evidently it wasn’t then, and sadly it still isn’t in the minds of some.

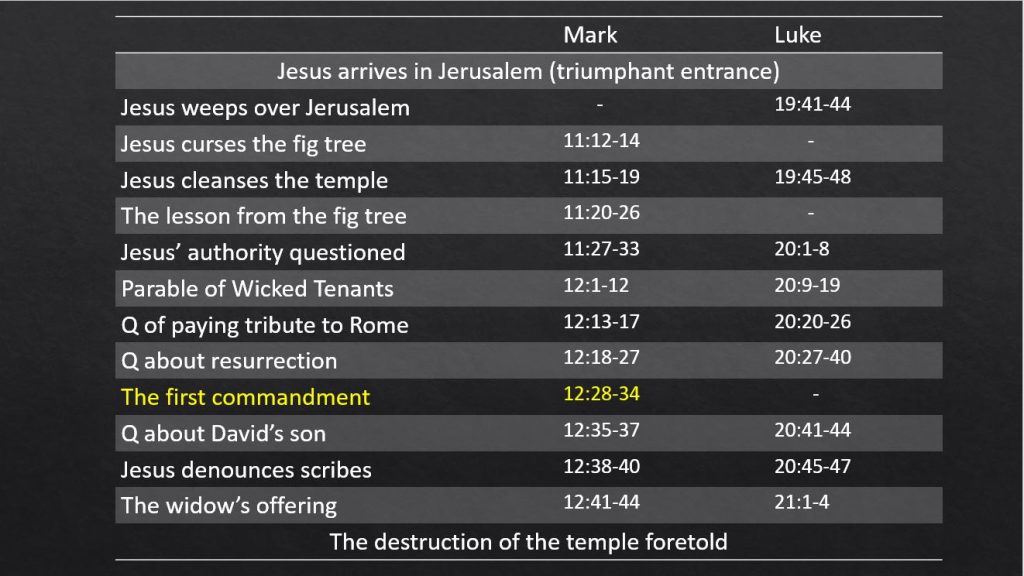

I came to the reading from Mark’s Gospel with that in mind and wondered, is there a sting in this tale too? As before, we need to consider some context for the readings. First, let’s consider the position of the story within the text. Mark places the story at the end of a series of clashes, discussions and debates between Jesus and the priests, scribes and elders just after Jesus’ arrival in Jerusalem. This group of stories only occurs in the gospels of Mark and Luke, and Luke has copied them in the same order almost verbatim from Mark. You can see the two sequences side-by-side. There are questions about interpretation of Torah: taxes, the concept of resurrection, the Messiah. There are questions about authority and conflicts with authority, both active and in parable form. Jesus both criticises and outmanoeuvres his detractors, with one exception – the scribe who in last week’s reading, echoed Jesus’ interpretation of the Torah as loving God and loving one’s neighbour.

I came to the reading from Mark’s Gospel with that in mind and wondered, is there a sting in this tale too? As before, we need to consider some context for the readings. First, let’s consider the position of the story within the text. Mark places the story at the end of a series of clashes, discussions and debates between Jesus and the priests, scribes and elders just after Jesus’ arrival in Jerusalem. This group of stories only occurs in the gospels of Mark and Luke, and Luke has copied them in the same order almost verbatim from Mark. You can see the two sequences side-by-side. There are questions about interpretation of Torah: taxes, the concept of resurrection, the Messiah. There are questions about authority and conflicts with authority, both active and in parable form. Jesus both criticises and outmanoeuvres his detractors, with one exception – the scribe who in last week’s reading, echoed Jesus’ interpretation of the Torah as loving God and loving one’s neighbour.

Mark’s inclusion of that passage emphasises two things for me. First, Mark’s Jesus is not condemning all scribes when he says “Beware of the scribes, who like to walk around in long robes and to be greeted with respect in the marketplaces…”; he has just congratulated one and told him he is not far from the kingdom of God. Secondly, he is pointing out that these debates over points of law and scriptural interpretation must be put in the context of the greatest commandments: to love God and to love one’s neighbour as oneself.

Another point of context here. While we may think of scribes as those who could write on behalf of the illiterate majority in those days, the scribes were also interpreters of the law. Ezra was described as “a ready scribe in the law of Moses” (Ezra 7:6) – those who could write or copy the Law could at the same time be interpreters of the Law. The Scholars Version of the Bible actually uses the word “scholar” in their translation, rather than “scribe”. When Jesus says the scribes “devour widows’ houses” (“prey on widows and their families” in the Scholar’s Version) this is probably a reference to their role in interpreting the law in public disputes. The wife’s rights were set out in a marriage contract, the ketubah, which included an amount payable at her husband’s death or on divorce. In general, a widow was allowed to dwell in her late husband’s house and receive her support from his estate. If the scribes interpreted the law unjustly, they might find excuses to deprive her of her rights. Remember, widows could not speak for themselves – it was a man’s world.

Today’s reading from Ruth skipped over an element of the story which relates to this. Before agreeing to marry Ruth, Boaz points out that there is another, closer kinsman who would have the obligation to look after Naomi and thereby have the option to buy her husband’s land. The kinsman says he will buy the land until he discovers that by doing so he would also become responsible for (“acquire”) Ruth, whereupon he makes excuses about complicating his own his inheritance and opts out. It could be this kind of arguing over widows’ inheritances by vested interests that Jesus has in mind. It is surely not compatible with following the first and second commandments.

With that in mind, we must consider next that the headings in our modern bibles are not part of the original text. The Greek text runs them all together and so the division between denouncing the scribes and praising the widow is an arbitrary one. Read as a single passage, the story of the poor widow could be a continuation or illustration of Jesus’ criticism of the unjust scribes. Why was the widow poor? As we have just heard, widows were to be protected under Jewish law, with very strong emphasis. Had an interpreter of the law deprived her of her rights? Why was the widow giving to the temple treasury? Probably, given the timing, she was contributing the ½ shekel tax required from everyone in the month before Passover, which paid for the sacrifices and the temple staff, with the surplus going to civil works. So, was it fair that the poor widow, who should have been protected by the law, was required by the temple authorities to give all that she had?

Remember, Mark was first an oral presentation. We can’t hear the tone of voice used in the performance of Jesus. Was it in fact originally a sarcastic comment, a criticism of a poll tax and a system which did not live up to its ideals? I think that Mark (and possibly Jesus) is telling a parable in which, like the book of Ruth, the story is ostensibly about the self-sacrifice and faithfulness of a widow, but with an underlying message which is a criticism of a lack of justice.

Perhaps despite the good intentions of the early Jesus followers, there was still a reluctance in some quarters to support the vulnerable. The letter of James, which was probably written during the same period as the Gospels, consists of a series of moral instructions attributed to James, brother of Jesus, (although this is unlikely) including showing no partiality between the humble and the rich. The fact that this needed to be written down implies that the opposite was happening. The later Epistles, attributed to Paul but certainly not written by him, attempt to rein back both Jesus’ and Paul’s radical inclusiveness and have a very negative view of women. One of these letters, 1 Timothy, includes several paragraphs which seek to avoid “the church being burdened” with widows: “Let a widow be put on the list if she is not less than sixty years old and has been married only once; 10 she must be well attested for her good works, as one who has brought up children, shown hospitality, washed the saints’ feet, helped the afflicted, and devoted herself to doing good in every way. 11 But refuse to put younger widows on the list, for when their sensual desires alienate them from Christ, they want to marry, 12… 13 Besides that, they learn to be idle.., and… also gossips and busybodies …16 If any believing woman has relatives who are widows, let her assist them; let the church not be burdened.” Well! It seems the early Christian church was not immune to the use of rules to justify injustice!

And how about us, today? Now that we have social security to provide for the widows and Oranga Tamariki for orphans, even migrant support for a small quota of refugees (one of the lowest per capita internationally)? Do our laws exemplify justice? Unfortunately, there is not always a direct correlation. If the Treaty Principles Bill has one small positive about it, it has encouraged more people to take a closer look at te Tiriti in order to refute the proposals which can on the face of it seem quite reasonable. Everyone should be equal? Who can argue with that? But we saw with the children’s talk that equality doesn’t necessarily result in fairness (justice). Efforts to tackle poverty can raise similar questions – If no-one in your family has ever been to university, if no-one in your family has ever had a permanent job, does treating all candidates equally give you an equal chance of achieving a degree? If we were all to pay equal amounts of tax wouldn’t that be fair? No fairer than the ½ shekel temple tax the poor widow couldn’t afford. If a business chooses to manufacture overseas because of lower wages, that may be legal, but the profits are not always shared justly. I’m sure that the richest people in the world for the most part conduct their business, gain their wealth, and pay their taxes legally (no doubt they pay lawyers enough to ensure this is the case), but does that mean they are just in their dealings with employees, other businesses and governments?

These are big issues; how can we change them? There are many ways of doing so, whatever our situation is. Some can march and raise their voices at protests. Some can choose where to invest their Kiwisaver funds. Some can afford to choose to buy clothes and food from ethical sources. We can all choose who to vote for!

If we agree with Isaiah that we should “Pursue justice, champion the oppressed, give the orphan his rights, plead the widow’s cause” (Isa 1:12); if want to follow Jesus’ example (in life, not death!); if we believe in the radical principles of inclusion that “the real Paul” (not his later editors) espoused; then we know that love is the beating heart of justice. Or, as Cornel West said, “justice is what love looks like in public”.