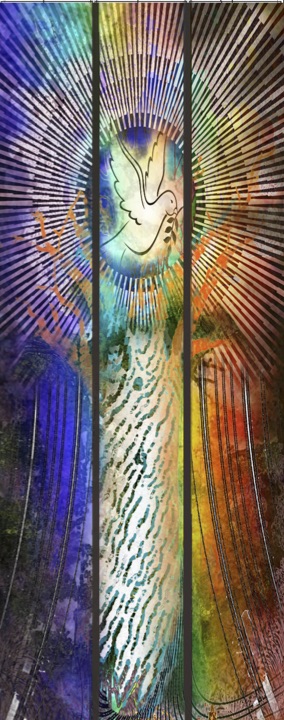

Work is underway on an exciting new and colourful window that will evoke a hopeful and inclusive message from The Chapel at Aldersgate to the busy Durham Street frontage. Symbols and images in the window’s design have been deliberately chosen to speak to people from a variety of faith backgrounds and none, filling three giant vertical panels, almost the height of the Aldersgate building. It is expected the window will be ready for Aldersgate’s Opening Celebration in February 2020.

We could only possibly afford such a large window of stained glass, because of the very generous support for the project by its designer and creator, Graham Stewart (Stewart Stained Glass), who sees the window as an important artistic, legacy project for the city.

Stained glass windows have always told stories, and this window is no different.

A stylised Rainbow provides the splash of translucent colours behind all the other images in the window. It stands for the colourful diversity of humanity and all who are welcome and celebrated in this building. As well as being a well-known symbol for LGBTQI+ inclusion, the rainbow is also associated with joy and playfulness (especially for children), and has had a place in legend, art and religion throughout history – probably owing to its beauty and pre-scientific difficulty in explaining the phenomenon. In Greco-Roman mythology it was considered to be a path made by a messenger (Iris) between Earth and Heaven.

In the dreamtime of Australian Aborigines, the Rainbow Serpent is the deity governing water, while in Hindu philosophy, the seven colours of the rainbow represent the seven chakras – from the first chakra (red) to the seventh chakra (violet). In Islam, rainbows only consist of four colours (blue, green, red and yellow) which correspond with the four elements water, earth, fire and air. Buddhists believe that the seven colours of the rainbow represent the seven continents of the Earth. More symbols of inclusion. The rainbow also has a key role for Jews and Christians in the story of Noah’s ark, as a powerful symbol of God’s universal and never-ending love and care for humanity, and in the Quran – though only briefly alluding to the story of Nooh, as a sign of protection and security from Allah.

The Rainbow also has a particular local link for Durham Street Methodists. When a group from Dunedin Methodist parish travelled to Christchurch in November 1996 to attend the induction of the Revd Dr David Bromell as minister of the Durham Street Methodist Church they brought this joyous song of inclusion, Rainbow People, by Colin Gibson, with them. (And Gibson named the tune ‘Durham Street’.)

From the base of the window flows a River of Life. In both the first and the last books of the Christian bible, the River of Life appears, first in the Garden of Eden, and finally through the middle of the Heavenly City, as a symbol of the source of life-to-the full, flowing from God, for the nourishment and healing of the people.

Water is considered a purifier in most faiths, with the Baha’i faith, Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, the Rastafari movement, Shinto, Sikhism and Taoism all incorporate some element of ritual washing. Immersion in (or sprinkling with) water is the central inclusive sacrament of Christianity (baptism); it is also a part of the practice of other religions, including Judaism (mikva) and Sikkhism (Amrit Sanskar). In addition, a ritual bath in pure water is performed for the dead in many religions including Judaism and Islam. In Islam, the five daily prayers can be done in most cases after completing washing certain parts of the body using clean water (wudu). In Shinto, water is used in almost all rituals to cleanse a person or an area (for example, in the ritual of misogi, or when approaching a shrine).

At the centre of the windows the flowing water becomes the rippled trunk of a Tree of Life – a religious symbol since Ancient Mesopotamia, often as a precious sign of all that nurtures humanity and offers life in its fullness. The Bo (or Bodhi) tree, according to Buddhist tradition, is the pipal under which the Buddha sat when he attained Enlightenment (Bodhi) at Bodh Gaya. In the sacred books of Hinduism (Sanatana Dharma), Puranas mentions the divine tree Kalpavriksha Kalpavruksham. This divine tree is guarded by Gandharvas in the garden of Amaravati, a city under the control of Indra, the King of Gods.

Etz Chaim, Hebrew for ‘tree of life,’ is a common term used in Judaism, including figuratively applying to Wisdom in general and to the Holy Book of the Torah in particular. For both Jews and Christians, the Tree of Life is mentioned in the Book of Genesis (along with the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil). In the Garden of Eden, after Adam and Eve disobeyed God by eating fruit from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, they were driven out of Eden, while remaining in the garden was the Tree of Life. The Tree of Life reappears in the last book of the Christian Bible, the Book of Revelation, as a part of a new garden of paradise, where access is then no longer forbidden. Some Christians also refer to the Cross (on which Jesus was executed), and even Jesus himself as the Tree of Life. The Tree of Immortality is the tree of life motif as it appears in the Quran, the only tree Islam mentions in the Garden of Eden, and also subject of Adam’s temptation. The concept of the Tree of Life also appears in the writings of the Baha’i Faith, where it can refer to the Manifestation of God, a great teacher who appears to humanity from age to age. And in more recent times the Tree of Life is a well-known and often cited story in the Book of Mormon. The vision includes a path leading to a tree symbolising salvation, with an iron rod along the path whereby followers of Jesus may hold to the rod and avoid wandering off the path.

For some the straight and strong tree in the window design may also evoke tī kōuka (the cabbage tree) as something of an indigenous ‘tree of life’. Their strong root systems help stop soil erosion on steep slopes and because they tolerate wet soil, they are a useful species for planting along stream banks – particularly useful in the swamps of Otautahi. Māori used cabbage trees as a food, fibre and medicine. The root, stem and top are all edible, a good source of starch and sugar. The fibre is separated by long cooking or by breaking up before cooking. The leaves were woven into baskets, sandals, rope, rain capes and other items and were also made into tea to cure diarrhoea and dysentery. Cabbage trees often point the way, as they were planted to mark trails, boundaries, urupā (cemeteries) and births, since they are generally long-lived.

Atop the Tree of Life in our window is a Dove, holding a small branch in its beak – perhaps an olive branch. Doves, usually white and often carrying a small branch, appear in many settings as symbols of love, peace or as a messenger. In the Hebrew and Christian scriptures, a dove was released by Noah after the flood, and it came back carrying a freshly plucked olive leaf – a sign of life, hope and new beginnings, as well as a sign of God’s care and protection for his people. The Talmud compares the Spirit of God to a dove that hovers over the face of the waters, while several of the Christian gospels describe how, after the baptism of Jesus, the heavens opened up to Jesus and he saw the Spirit of God descend like a Dove. So the Dove is also a symbol of God’s presence or blessing. The early Christians are credited with originating the use of the Dove as a symbol of peace, a use which has spread very widely including pacifists of different faiths or none. For many Moslems, doves and the pigeon family are also respected because they are believed to have assisted the final prophet of Islam in distracting Muhammad’s enemies outside the cave of Thaw’r, in the great Hijra.

Māori developed a sophisticated structure of beliefs and customs about the birds of this land. Larger birds like the harrier (kahu) and morepork (ruru) had tasks in the Maori world also as messengers to the gods in the heavens, winging their ways there along spiritual paths. They were the mediums used by tohunga experts to communicate with the gods.

2 responses to “Stunning, new inclusive image to light Aldersgate”